France’s new National Archives hits the ‘burbs|A series of stacked blocks create a light-looking frontage|Antony Gormley’s Cloud Chain|The exterior, showing the main building and its “satellites”|The auditorium|Spacious research areas||

France’s new National Archives hits the ‘burbs|A series of stacked blocks create a light-looking frontage|Antony Gormley’s Cloud Chain|The exterior, showing the main building and its “satellites”|The auditorium|Spacious research areas||

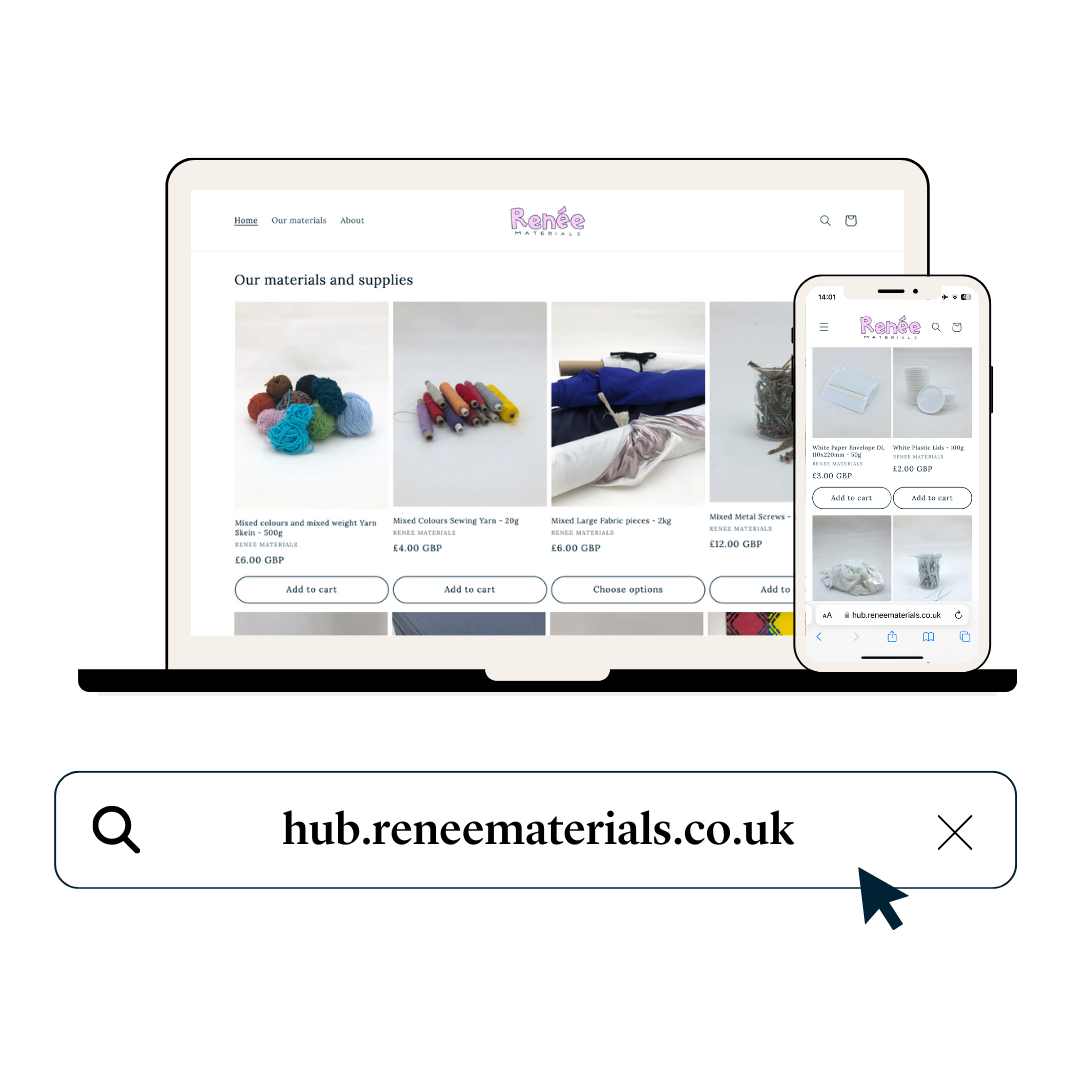

In Futurama, the quirky sci-fi animation sitcom dreamt up by Simpsons creator Matt Groening, the series protagonist visits an imperious Speerian building – the Mars Library. Inside he finds that instead of endless shelves of books, all the world’s great literary works are compressed into two tiny disks labelled ‘fiction’ and ‘non-fiction’ – a vision of how life might be in the 31st century. But back in the 21st, despite the arrival of cloud computing and the oft-predicted demise of the library, a need for physical storage space prevails. Offering no better illustration of this is the newly completed National Archives of France by Italian architects Studio Fuksas. It’s a hefty 110,000sq m beast intended to consolidate the country’s post-revolution documents into one building, thereby replacing four existing outposts dotted about the city. Spanning the terms of four French presidents beginning with François Mitterrand, the building has been a long time in the making and finally opened in January this year.

Originally, the bulk of the archives were housed in a mansion, the Hôtel de Soubise, in Paris’s Le Marais district, the city’s old aristocratic quarter. This grand dame of a building will retain (rather appropriately) the pre-revolutionary archives. The rest are moving to the new site some seven miles north, in Pierrefitte-sur-Seine. A nondescript ’burb, the area’s blandness was precisely what made it so appealing. “The idea was to make a generator of urbanisation,” explains project architect Dong Cui. “There is not much around this area apart from some houses and apartments. They needed a big public centre, a cultural building to attract people who live in Paris to this new site.”

Faced with a brief for a building of considerable mass, the practice devised a design of two halves. The journey begins with a series of six cantilevered blocks, either stacked on top of each other or propped up on stilts. Appearing somewhat arbitrary in arrangement, these wafer-like elements, which Cui calls “satellites” create a tremendous permeability at ground level as well as a dynamic architectural presence. They in turn are backed by a much larger, largely windowless monolithic block, inside which lie 220 archival stock rooms.

The satellites feature floor-to-ceiling glazing wrapped in a diamond-patterned aluminium skin. The motif is a recurring theme in the architect’s work (the swooping Lycée Georges Frêche in Montepellier is a good recent example). Cui explains how the buildings’ two radically different forms required this unifying design language: “We needed an element that joined the satellites with the monolith. You can find this diamond shape everywhere on the building.”

The balancing blocks provide a clearly defined structure for the building’s multiple functions – housing offices, a 300-seat conference room and exhibition space – while ensuring a easy delineation between public and private space. To this end, the building has an obvious public entrance on the easternmost wafer that leads to a lobby, while the staff entrance is recessed deep into the heart of the complex. The conference room is a cave-like space with black walls, floor and ceiling, pitched against bright red cinema-style seating.

Running around the building is a moat, which forms a natural barrier between the archive storage and the satellites while enhancing the public/private separation. Cui explains the idea was to bring a softer feel to the complex, but it seems a pity not to have used these areas for outdoor green space. That said, its contemplative nature fits with the building’s studious programme. Rising eerily from the moat is a spidery metal sculpture by Antony Gormley that twists along the water drawing on the facade’s materials and aesthetic.

Umbilical bridges cross the pools to attach the first half of the complex to the monolithic silver box. These skywalks ensure that staff can shuttle between their offices and the archives without mixing with the hoi polloi. The ten-storey archive dwarfs its sister structure and indeed the surrounding context, so rather than use heavy masonry or glass, the architects attempted to achieve a calm yet stimulating presence using anodised aluminium cladding. “We needed something light, not too heavy for the urban context,” says Cui. “We looked at a lot of different materials, like polished steel, but compared with those the anodised aluminium reflection is quite slight. It changes with the conditions. On a clear day, it looks like it is made from the sky.”

The monolith is almost completely covered in the panels save for the 160-seat reading room, where transparent slivers allow sunlight to penetrate the interior. With low intimate ceilings and warm wooden floors, the reading room is designed for quiet research. It is proving a popular space, according to Cui.

It is perhaps too early to measure the building’s success – after all, the staff has only just moved in. Given the archives’ relative isolation (especially compared to its fomer central location), one element that might prove a worthwhile addition is a restaurant, says Cui. “There is a cafeteria, which is OK for something simple, but with more and more people working in the building there should be a restaurant. At the moment they [the client] do not want to do something that might create discord. They want to keep the building quite calm. Functionally, though, [the building] has no problems.”