James Woudhuysen, Professor of Forecasting and Innovation at De Montfort University, Leicester, and Paul Maloney, of the UK’s largest union, the GMB, both agree that keeping tags on workers is bad. But what’s the best way to put a stop to it – highlighting health and safety concerns or waving rude signs around?

James Woudhuysen, Professor of Forecasting and Innovation at De Montfort University, Leicester, and Paul Maloney, of the UK’s largest union, the GMB, both agree that keeping tags on workers is bad. But what’s the best way to put a stop to it – highlighting health and safety concerns or waving rude signs around?

Paul Maloney: I represent people in workplaces like call centres where there are 400 to 600 people working and calls are recorded and monitored. Often, people are not told that this is happening or they think their calls are being recorded for training purposes. Within the Automobile Association, for example, once you log on, everything you do until your shift finishes, including breaks, toilet time, down time, voicemails, telephone conversations, keyboard strokes, is measured to the second. This is used to assess performance, time management and discipline and will have an effect on pay and grading. This causes distress to staff and sickness. It’s an intrusion on an individual’s life.

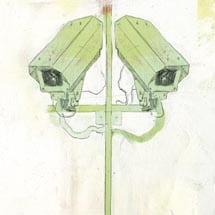

James Woudhuysen: I think I follow you nearly all the way on this. I wouldn’t play up the stress so much or the health aspects. I would put it more pugnaciously. Management should not have the right to keep data on every movement and operation conducted by the workforce. That is intrusive. I think the call centre case is particularly data intensive because it’s much easier to measure in every way. Every delivery driver and transport employee is also subjected to more of this dehumanising and impersonal measurement. It says little about their human or qualitative contributions. I wouldn’t want to see this pursued in the courts or with extra-judicial inquiries, not because I think it’s a constraint on business, but because it doesn’t allow employees who have really had a bad experience with it to move on from that experience. I think workers in America simply put a sheet of A4 in front of the cameras, saying “Bugger off, we know you’re watching us!” which I think is better than a chase through industrial tribunals and redundancy procedure, if it gets a result.

PM: But that’s gross misconduct and once he or she has a dismissal on the record, they won’t be employed again. Some employers need to protect their property and the customer and individual – such as in Accident and Emergency in a hospital where cameras protect the staff and the public – but when it’s being used covertly, that’s an issue for me. I have also agreed with managers in the nuclear installations. With terrorism and its potential, we have set up an agreement with the unions that we will allow surveillance around nuclear power stations. But it’s the tracking of individuals to drive profits, that’s where it becomes intrusive and dangerous.

JW: I am not sure I go with you there. Maybe there’s a case for nuclear installations, but I am not sure that families or patients need filming at hospitals or in A&E. I don’t know that does staff any favours. Sometimes there are drunken individuals but once one concedes the argument for dataveillance of the public, then it becomes harder to fight against surveillance of the workforce. Additionally, with all of the data, the ability to use or even find the data on anybody seems questionable. Although I resent the intrusions, I wouldn’t want to overestimate the effect on workers – making them into victims – nor would I want to overestimate how rationally or sensibly management can work with that data. Often the use of measurement stuff can be a displacement activity for management from the more difficult job of providing better customer service. It’s much easier to put a CCTV camera up at reception than to get better recoveries on a cancer ward. I think workplace surveillance of staff is bad news. It needs resistance, though not court cases, but there’s no need to be too paranoid. Management’s collecting this stuff instead of doing something useful. We see that in the NHS where targets come before curing a patient.

PM: I am saying that security cameras in hospitals are there to protect people. If a member of staff is assaulted, they would be able to call help quickly.

JW: It might be wiser to have a burly security guard there! He’s going to be much more useful in Homerton Hospital at two in the morning. But do we want to build a society of trust where we believe that the majority of people do behave themselves in a social way or do we believe that anti-social behaviour is so widespread that – apart from ourselves, of course – we endorse it everywhere else? Even in Sellafield or somewhere, I would urge anyone to get that into perspective to avoid surveillance.

PM: I am glad you mentioned anti-social behaviour, James. I think the most anti-social part of this is where you get a company like the AA who uses dataveillance all the time.

JW: It’s antisocial and disrespectful. I think the main thing is to challenge the culture of paranoia and distrust and to challenge the response of victim-hood. It’s about time the trade unions recognised that was an important issue as well as better service, rather than a hundred key performance indicators.

PM: The question of paranoia doesn’t come into it because the figures are taken on a monthly basis and if you have spent any more than X amount of seconds on a call, you are questioned as to why you have done that. Then the recording is played back and they are saying: “This is why! You have spent too long on the call talking!” That’s not paranoia, that’s mental humiliation and to allow individuals to get away with that in 2006 is ridiculous.

JW: No, I’m not saying those members are paranoid. Iffy managers and well-meaning managers can both be intrusive, dehumanising and demanding. It is outrageous. I am saying the response – how the unions handle it and the media, too – is more a case of ridicule, rather than defensiveness. I wouldn’t say: “We are totally browbeaten by this.” I would say: “Well, why do you want to measure all this shit?! How’s that going to help you? Where’s the result? How are customer relations being improved by you doing all this rubbish? Haven’t you got something better to do?”

M: This is the type of thing we are battling against and the union has been described as “over militant” because we are trying to defend the member on this one. When a member gets dismissed, he or she has a right to go before an employment tribunal. We have got a right to disclosure of the information that they have against them and we finish up in front of tribunals with great big machines and tapes and dataveillance and microphones and the rest that we didn’t know existed.

JW: That’s bad. My point is that unions are not militant enough and they don’t use the right arguments to win. I think an atmosphere of trust towards customers and employees is proper. I think there should be ridicule towards these attempts to manipulate, and of the courts to believe that they can provide satisfactory redress without delay for worker struggles. In 30 years of activism, I have found that little confidence in the courts was the best policy. I think an attitude of adult scepticism is the proper riposte.