The EN 1335 test|The Diffrient World chair, which failed the test, essentially because it was too lightweight|Herman Miller’s Sayl chair needs a different gas lift in the EU, to meet height range requirements||

The EN 1335 test|The Diffrient World chair, which failed the test, essentially because it was too lightweight|Herman Miller’s Sayl chair needs a different gas lift in the EU, to meet height range requirements||

US furniture makers say our regulations are so stringent they stifle innovation, while the lumbering pace of EU legislation can’t keep up with changing workplace practice. Are there too many rules?

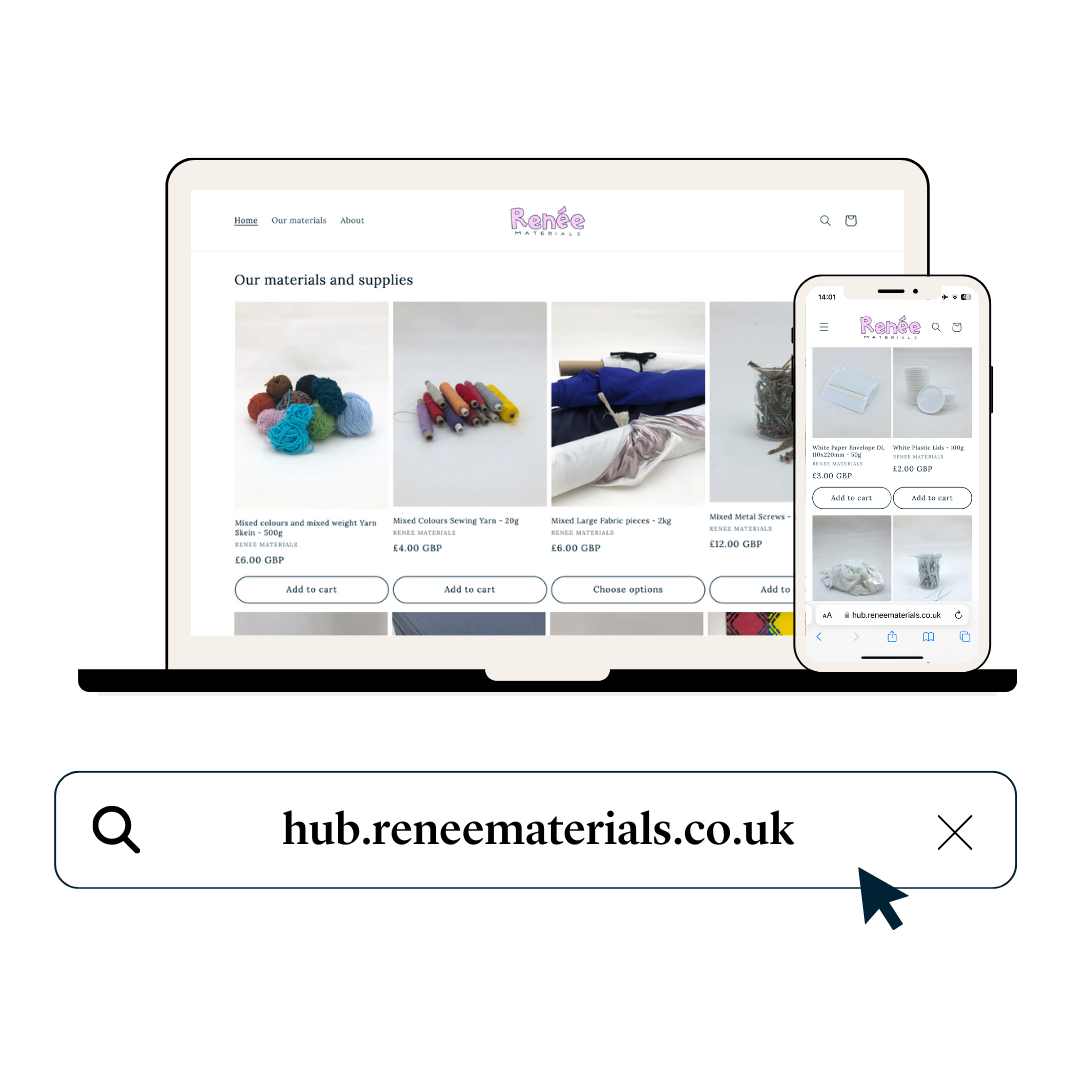

On 8 June one of the greatest modern designers, Niels Diffrient, died. While the American’s work never penetrated the wider public consciousness like, for example, Charles and Ray Eames, his mastery of ergonomic design commanded huge respect within the industry. Diffrient was universally recognised for his work with Knoll and later Humanscale – the latter a small but dynamic US company whose ergonomic leanings made the pair a perfect match. The partnership created some of Humanscale’s most successful products; the Diffrient World chair (left), for example, launched to the US market in 2009, was incredibly well received, winning plaudits for its ultra-lightweight frame. But when it reached Europe it failed to pass the European Standard EN 1335 ‘forward overturning’ test.

Designed to test stability, EN 1335 is intended to simulate someone sitting too far forward in the chair in something the EU calls ‘acceptable misuse’. If it falls over, it is deemed unsafe and it’s back to the drawing board. Diffrient World’s lightweight frame put it at a serious disadvantage compared to heavier competitors. Its failure was surprising. How could a product be safe in one country and not in another?

Levent Caglar, senior ergonomist at FIRA (the UK body that ensures products meet European Standards) says the misunderstanding lies in the different testing methods. “In the US, it is much more about putting a lot of weight on a desk or chair. In Europe, we try and simulate how people use the chair,” he explains. “People do sit on the edges, even though they shouldn’t.”

The saga, which dragged on until 2013, eventually concluded when Humanscale added extra weight to the chair in order to pass the test. For a small company whose survival relies on it being ahead of the curve, the process seemed absurd. “We spent a lot of money making it incredibly simple and incredibly light,” says the firm’s CEO Bob King. “It uses less materials, it uses less when transported and it moves more easily when you are sitting on it.

“Given the nature of the test, our chairs tip more easily than chairs that weigh an extra ten pounds, but that is irrelevant because it is tested in such an artificial way, for example, without a sitter’s weight. The fact is, our chair is no more likely to tip than any other chair when someone is sitting in it.”

Caglar concedes that, for chairs with soft-edged or mesh seats (like Diffrient World), people are less likely to sit near the edge of the seat as they would when a chair features a hard underframe. The test replicates a weight being placed 60mm from the front of the seat, and Caglar says that “it could be argued that 60mm is too far forward. This may be a topic to be pursued when the standard is revised in 2014/15.” This is likely to be scant consolation for Humanscale, which feels its ability to innovate is being stifled by European Standards, to the detriment of end-users.

Part of the problem, according to Caglar, is that the US is not regulated as tightly as Europe. “They [the US] have no regulations affecting the office environment like we have. EC regulations say you must have minimum requirements for chairs and tables.” Which begs the question, is the European market over regulated? Given the famously litigious nature of US society, a chair deemed safe by Uncle Sam must surely be OK here.

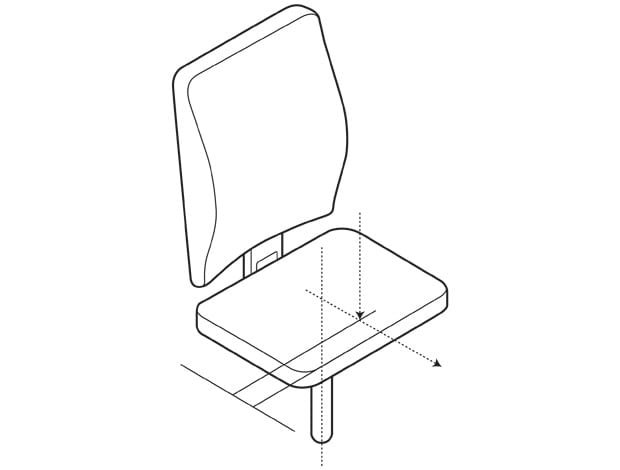

Bob Rhodes, conformance manager at Herman Miller in the UK (pictured left: Herman Miller’s Sayl chair) sympathises with Humanscale’s experience, recalling similar stumbling blocks earlier in his career. “We used to bring in a lot of products from the States, and because it was Herman Miller, everyone assumed it would meet every standard we could throw at it. But actually it doesn’t because they are different. For instance, over here we are much more focused on things like finger traps than the Americans. At the end of the day it comes down to what someone’s view of ‘safe’ is”. Of course, no one wants a chair that squeezes people’s fingers, but when it’s two pieces of foam colliding, one could reasonably assume the damage to someone’s pinkie will be minimal. Nevertheless, these standards must be met.

Rhodes says a global mark would make life a whole lot simpler, but Europe’s fragmented nature means any simplification is likely to take a considerable amount of time, if it is possible at all: “At the last meeting about regulations, there were 20 delegates from eight or nine countries and they all have their own ideas. You get some idea of what the European Parliament must be like.” Rhodes agrees that some of the dimensional standards, first put forward in 2000, are due to be updated: “We should have something coming forward in the next two years, but I am not a betting man.”

The elephant in the room is the protectionist argument. Countries have a vested interest in ensuring that their own furniture standards are so extreme that foreign companies will not invest in the tooling to make chairs for that particular market.

Saschia Thiesen, a director at Haworth, points out the glacial pace at which standards are updated means that the current framework is out of touch with changing technology. “In Germany, the norms say a desk has to be a minimum of 160x80cm wide otherwise you have too small a surface to work on ergonomically. I would agree with that when we had huge monitors and pedestals, but today we have laptops. Of course, I am allowed to sell a desk smaller than this. But if I have to check the box for a key account to say that it meets all the regulations, I cannot do it.”

For King, the dimensional regulations (which for chairs were drawn up in the 1980s) are outdated, anachronistic and should be done away with. The key example King gives is the regulation that stipulates an armrest cannot come within 100mm of the front of the chair seat, which restricts the product’s adjustability. “If you adjust the seat back as far as you can and the armrest forward, of course you are going to come within 100mm. A lot of these dimensions are based on older philosophies that keep people in relatively fixed postures. We now realise that fixed postures are not comfortable or healthy. If you provide a lot of adjustability, you are going to bump up against these standards.”

Caglar explains that the armrest dimensions are there to ensure that the vertically challenged can get close to the desk while still using the backrest: “The 100mm may or may not be correct but that is the essence of it.” That said, highly adjustable chairs seem less likely to prevent this scenario than allow for it.

It is hard not to sympathise with both Caglar and King. Both strongly believe that standards are necessary to ensure safe and good quality products. The source of King’s frustration is the European Regulations as opposed to the body charged with performing the tests. For his part, Caglar must negotiate and consult with a myriad of concerns, including the Americans if he is to help flesh out updated and relevant sets of standards. A more dedicated man you are not likely to find, but his task seems labyrinthine.

In the end, Diffrient lived to see his chair cleared for the European market, albeit not quite in its original form. One feels that if companies can continue to truly innovate, something has got to give.