A “forest clearing” of green sofas and suspended wooden beams|”Floating” glass-clad meeting rooms, broken up by the steady glow from giant light boxes|The “forest clearing” area, with delicate leaf-like tables and suspended timber beam lights|Tending the kitchen garden: green is very on-brand|Dubbed the monastery, this CNC-cut box is a place for deep thought (and secret phone calls)|Oak reading boxes turn a blank corridor into useful spaces||

A “forest clearing” of green sofas and suspended wooden beams|”Floating” glass-clad meeting rooms, broken up by the steady glow from giant light boxes|The “forest clearing” area, with delicate leaf-like tables and suspended timber beam lights|Tending the kitchen garden: green is very on-brand|Dubbed the monastery, this CNC-cut box is a place for deep thought (and secret phone calls)|Oak reading boxes turn a blank corridor into useful spaces||

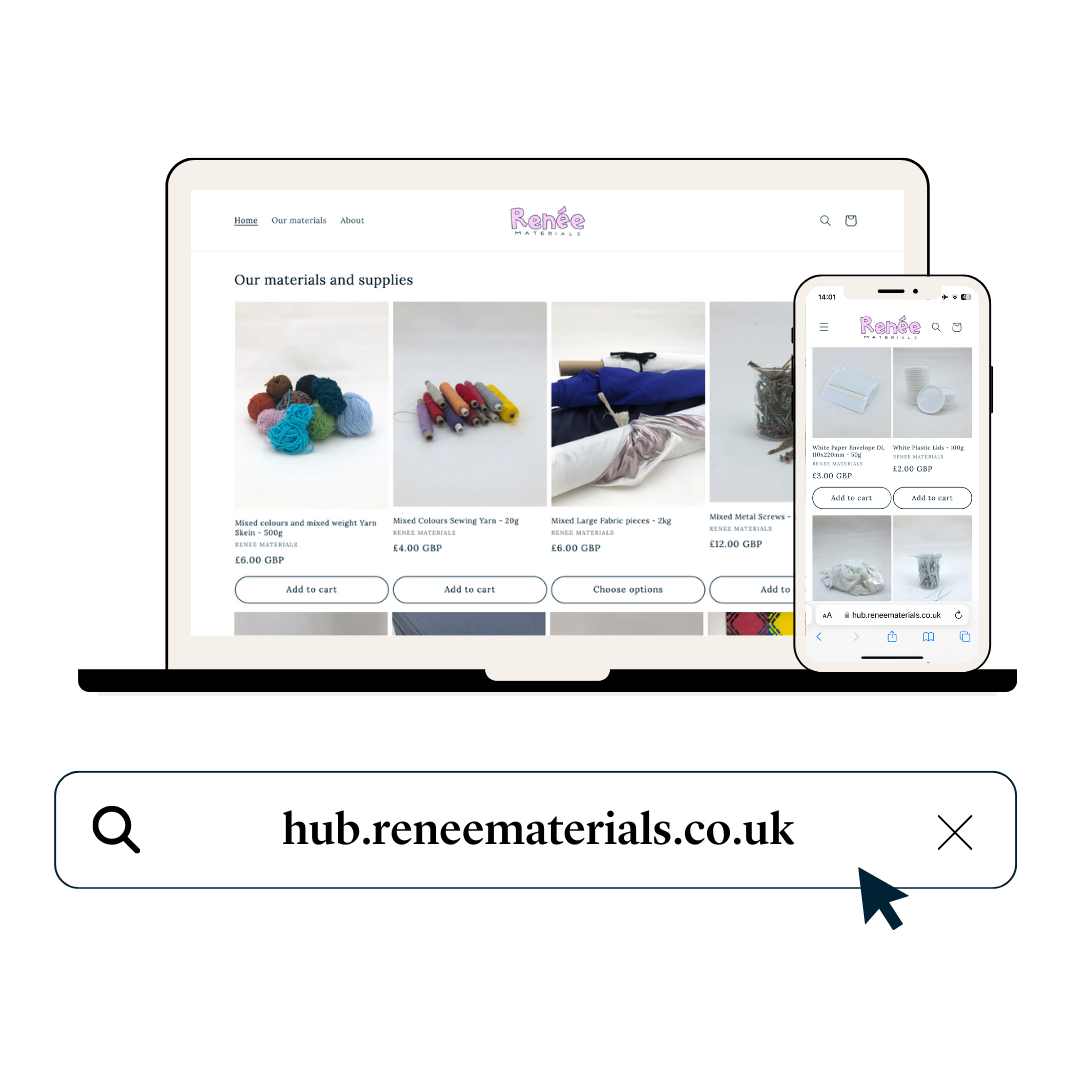

Internet companies are vague and mysterious entities: it can be hard to work out what they actually do. Architects seem to be aware of this too, and when their client’s product exists in web space there is seemingly less to inspire them as a starting point. In the past they’ve adopted a number of approaches, from questionable node graphics to glassy meeting boxes and the obligatory exposed ductwork. Skilfully and thoughtfully weaving in some of these elements, Norwegian practice Eriksen Skajaa Architects reinvented a challenging space for website consultants Netlife Research. Located in downtown Olso, the building presented a myriad of problems. First off, the ceilings are limbo-dancer low, just 2.2m in places. Compounding this was a deep floorplate that swallowed up most of the sunlight. The architects alleviated the slightly gloomy space by laying a white rubber floor and painting the ceilings and steel columns the same colour. Capitalising on this perfunctory manoeuvre, they installed a series of light boxes that divide the space between the glass meeting rooms, creating a glowing ambience while also ensuring the necessary privacy for a business whose day-to-day work is testing and refining clients’ websites. “The repetition creates a lot of depth,” says architect Arild Eriksen. “They [the lightboxes] are quite visible from wherever you are.”

The glass meeting rooms appear to gently float between the ceiling and floor thanks to a strip-light running around the base, which helps create the illusion of space. Aware that too much white space could result in a sterile-looking environment the practice constructed monolithic black walls as a contrast. A closer inspection reveals frameless doors secreting more private meeting rooms. “The black space is quite strict; it’s quite cavernous,” says Eriksen.

With these foundations in place the architects moved on to the second part of the brief, the client’s need for a mix of creative and quiet spaces. “Our mission was to maximise the feeling of height and light, but also they wanted these different creative areas,” says Eriksen. They came up with four areas based around a garden theme: monastery, park, kitchen garden and forest clearing. Visitors experience the first of these, the forest clearing, upon entering the office. Clusters of vertically suspended wooden beams partially enclose a waiting area furnished with soft seating. Again experimenting with light and shadow, the architects hollowed out the trunks of these “trees” and, by installing lighting in each, beams of light shoot out across the floor. Green sofas and diminutive leaf-like tables enhance the forest feeling while the beams break up and define what would otherwise be a bit of a nothing space.

Most peculiar of the garden themes is the monastery, a wooden box smack in the centre of an expansive room. It’s intended for private phone calls and for serious thinking time, and, despite the nods to postmodernism, it’s a peaceful, almost solemn structure. “Monasteries are the best places to go to retreat and relax. The modernism of 2000 got rid of inspiration from classical architects,” says Eriksen. “We wanted to use something that was a contrast to all the glass boxes and all the black and white.” The exacting finish is the result of choosing prefab over on-site construction: “It was a nice way of experimenting with CNC wood cutting.” Green is a strong feature of Netlife’s branding, and so, for the kitchen garden area, Eriksen snagged some old grow lamps from a nursery and dangled them above a smattering of potted plants.

The architects extracted maximum use from the building. A long corridor, ordinarily negative space, was cleverly transformed by adding oak reading boxes to the window sills. Staff can perch here and work from their laptops. Although the client saw the benefit in these creative flourishes there were certain elements that didn’t make the cut. Originally the forest was to continue throughout the office with little clearings for the different workspaces – an intriguing idea inspired by Japanese architect Kengo Kuma and Junya Ishigami, but ultimately discarded. “It pretty much would have filled up the space,” says Eriksen.

Most impressive, though, is this project’s timescale. From initial sketches to completion took just eight months, with any issues along the way exacerbated by Netlife Research’s swelling ranks – the company grew from 25 members of staff at the start of the project to 40 by its end. Maintaining quality control at this velocity was tough, admits Eriksen; on a few occasions the architects arrived on site to find that, in their haste, the builders got ahead of themselves. “We were drawing as they built and there wasn’t much time to discuss the details. We had to get them to tear down

a wall because it wasn’t drawn yet.”