The copper roof makes an arresting contrast with the Georgian brickwork|Recessed strips of LED lighting pick out the folds of the ceiling|Light oak flooring and whitewashed walls result in bright, crisp interiors|Exposed steelwork is painted in red oxide to give a semi-industrial look|Underground, a former silver vault has been reborn as a meeting room|The wood-panelled boardroom in the original Georgian building||

The copper roof makes an arresting contrast with the Georgian brickwork|Recessed strips of LED lighting pick out the folds of the ceiling|Light oak flooring and whitewashed walls result in bright, crisp interiors|Exposed steelwork is painted in red oxide to give a semi-industrial look|Underground, a former silver vault has been reborn as a meeting room|The wood-panelled boardroom in the original Georgian building||

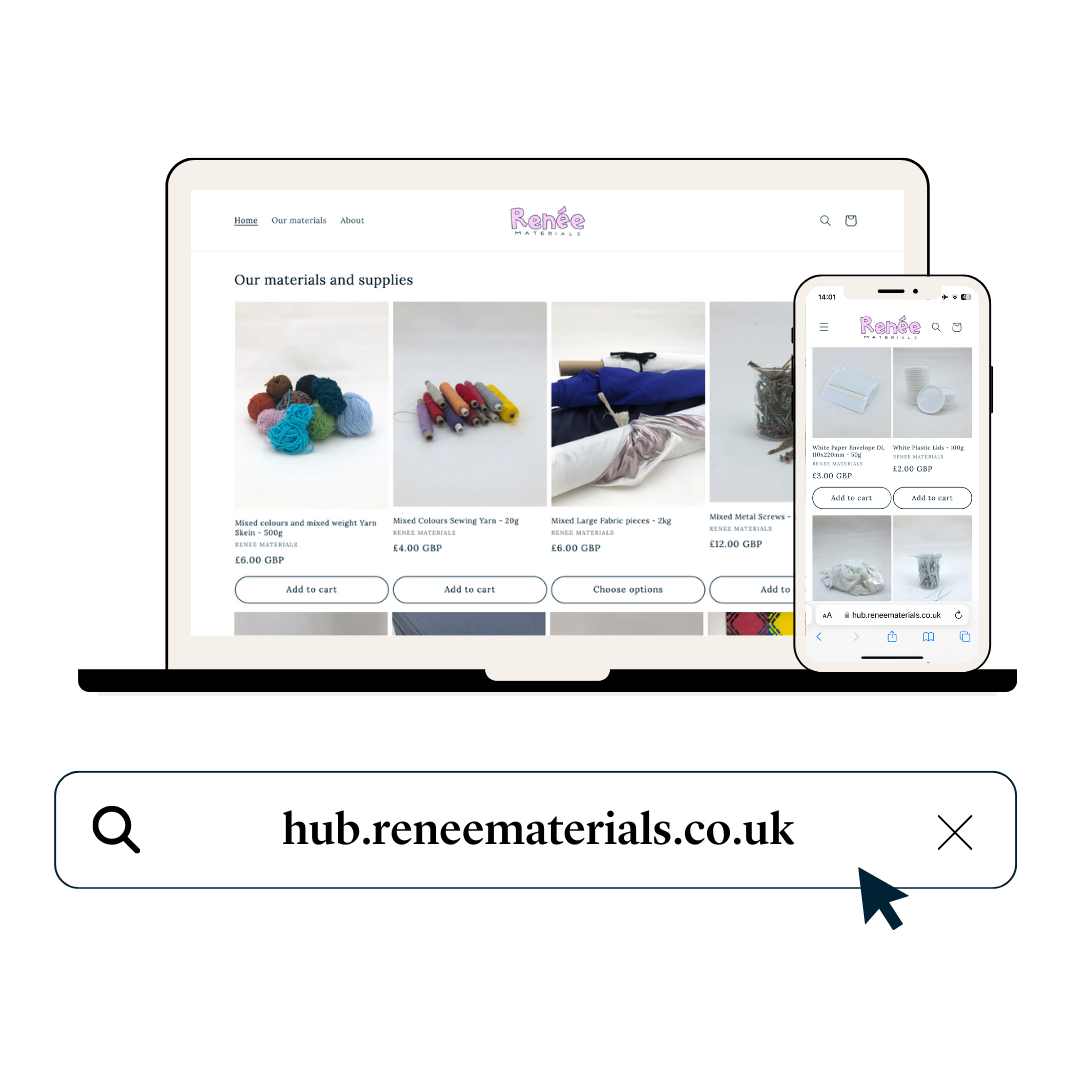

Emrys Architects extend GMS Estates’ Bloomsbury offices with a copper-roofed structure that compliments the existing Georgian bricks and folds like a piece of origami to fit existing party walls.

A grand facade in Bloomsbury hides a quirky office extension by Emrys Architects that, despite its arresting copper roof, sits comfortably alongside the Georgian brickwork. From the outside of the building, 32-33 Great James Street could be a private residence, and indeed the building, which GMS Estates has occupied since 1925, must feel a bit like home. However, it had become a little dog-eared.

“There were levels all over the place and annexes patched up from damage during the war. It was pretty ramshackle,” says practice director Glyn Emrys.

Anything this bold usually results from a tried-and-trusted working relationship between client and architect, and sure enough the bond between Emrys and GMS had already been sealed over a 15-year period collaborating on various projects.

Work to the existing reception and adjoining corridor entrance was nothing more extensive than some mild restoration of the existing fabric. The real challenge was unifying the disconnected warren-like office spaces beyond. From the outset, the client was clear that pastiche architecture mimicking the Grade II*-listed building was not desirable, which prompted no counter argument from the architects.

“The client was clear that mimicking the listed building was not desirable.”

Initially, Emrys developed plans for an undulating seeded roof punctuated by round skylights. Though the design delivered the volume and space required, it was flawed. “They [GMS] called it the ‘Teletubbies scheme’,” says Emrys. “To maximise the ceiling height we needed a curve, but because of where it was the seeded roof would struggle to survive.”

Following a rethink, the architects proposed a two-storey structure in place of the existing annex with a roof that took its irregular shape from existing party wall demands. The plan got the thumbs up from both GMS and Camden Council’s design conservation officer.

“We actually built this floor first and then mined down underneath so we had a working platform. The roof is held together by a steel ring beam,” says Emrys.

Recessed LED strips following the join of each triangular copper roof element light the workspace and enhance its faceted structure. Light, or lack thereof, was a problem in the original offices, so Emrys and his team installed triangular glazing in each corner adjoining the neighbouring brickwork. In a reference to the dormer window on the original annex, a window protrudes into the void at first-floor level.

Internally, the architects capitalised on the combination of new LED fixtures and daylight by laying parquet flooring in a light oak and whitewashing the walls. Steel uprights painted a striking red oxide, a colour repeated on the furniture, inject the space with a certain raw energy. The offices are heated and cooled with an air-source heat pump and the vents are painted the same shade of red.

The result is a bright, temperate and generous workspace (the ceiling climbs 4m at its highest point), which the seven or so staff dotted about the floor seem to be enjoying. At the far end of the office is a cantilevered wooden stair leading to the lower offices. Here, the architect was confronted by a barrel-ceilinged brick silver vault, which Camden Council’s planning department demanded should stay.

What might have proved an irritant was made a virtue by Emrys Architects; they dug down to introduce a lower floor level, thereby transforming the structure into an intimate – though with its monumental steel door, undeniably bunker-like – meeting room.

At the very least there is no danger of being overheard during crucial discussions. “It is usually easier just to have a clean floorplate but having to work around this worked quite well,” says Emrys.

A pair of glazed doors that lead out to two small paved areas draw in much-needed natural light, while exposed ceiling joists, finished in discreet limewash, chime with the chevron parquet flooring. One can access the townhouse from either floor of the new extension.

Upstairs is the original boardroom, which, with its wood panelled walls, austere portraiture and ancient typewriter displayed in one corner, provides the starkest contrast between old and new. A bespoke modern fixture by Cirrus Lighting (which supplied the LEDs for the whole project) replaces tired chandeliers.

Emrys is quick to praise the contractor, DDC, which managed to execute the whole job via a small doorway below the pavement on Great James Street – bags of rubble, new materials and machinery all came in and out of here. The 300-year-old foundations coughed up some unexpected challenges. For example, the brickwork extended much farther into the earth than expected, and elsewhere the excavation revealed an old Georgian soakaway that had to be dealt with.

Factoring in the project’s occasional unpredictability and the radical transformation of the working environment, the project’s £1m price tag looks like a bargain. Emrys Architects has demonstrated with this project how much can be achieved when imaginative design, technical know-how and sound project management align.