EA 104 Chair: Stalwart of many an architect’s office. Charles and Ray Eames’ EA chair was designed in 1958. This is the EA 104, one of three released versions that Vitra bought in 2014|Another Vitra re-released, this exuberant ottoman was designed in 1967 as part of Alexander Girad’s rebranding exercise for Braniff International Airlines, which included everything from the airport lounges to matchbooks||

EA 104 Chair: Stalwart of many an architect’s office. Charles and Ray Eames’ EA chair was designed in 1958. This is the EA 104, one of three released versions that Vitra bought in 2014|Another Vitra re-released, this exuberant ottoman was designed in 1967 as part of Alexander Girad’s rebranding exercise for Braniff International Airlines, which included everything from the airport lounges to matchbooks||

In uncertain times, manufacturers prefer to remake the classics rather than invest in R&D, but is it sustainable?

Due to the vagaries of public transport and difficulty of transferring to Terminal Four at Heathrow, I contrived to miss my flight to the Salone del Mobile in Milan this year.

Strangely, and bearing in mind I’ve been to every edition since 1996, I didn’t really miss it. In part thanks to new media, – the technological holy trinity that is Twitter, Facebook and Instagram – you still get to see absolutely everything. But it’s also because in recent times the major manufacturers have become increasingly conservative, relying on a coterie of big name designers or updating classic pieces rather than investing in something genuinely new. Meanwhile, in the column I write for this magazine I’ve found myself reviewing revived pieces by the likes of Lina Bo Bardi and Fred Scott.

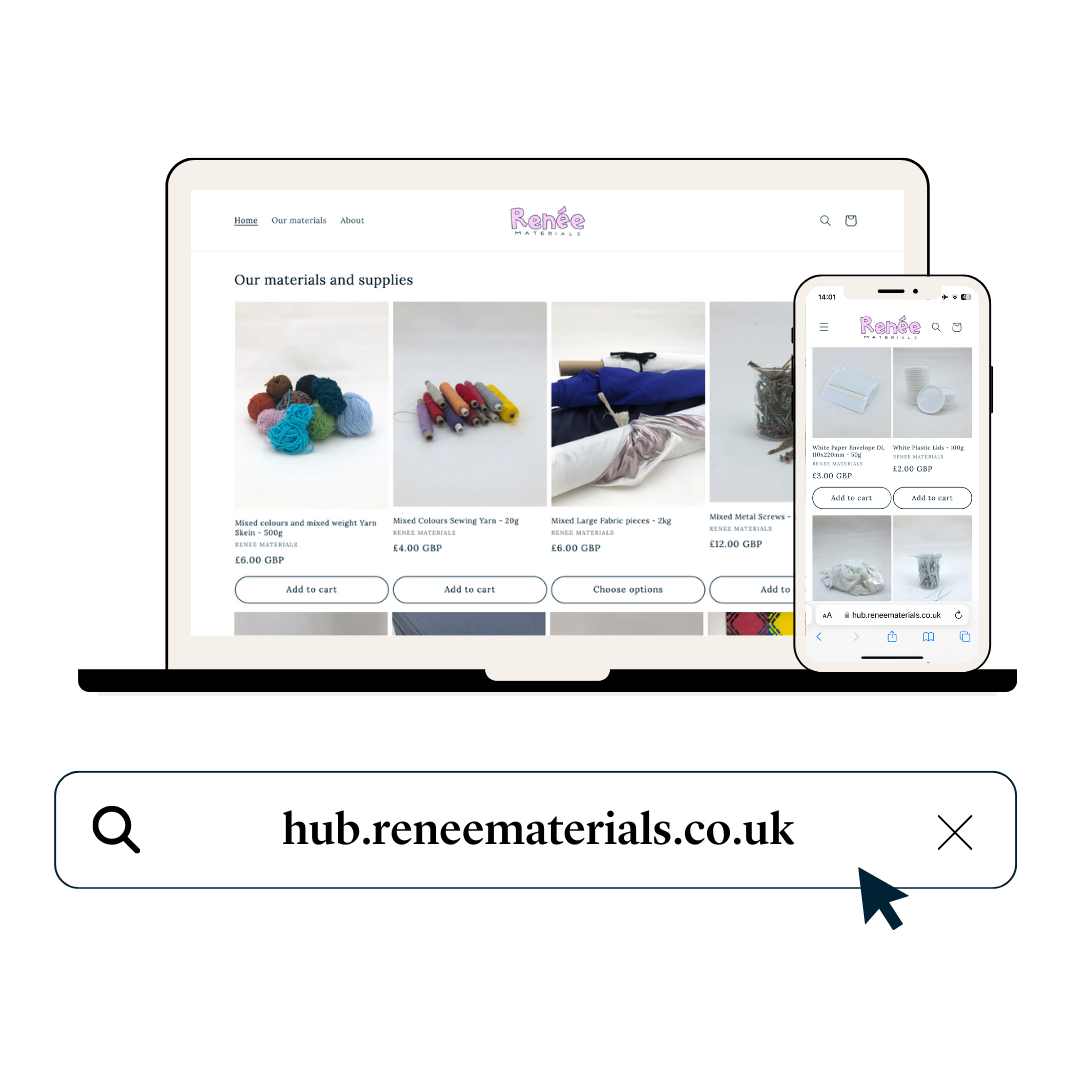

Elsewhere, Cassina has released a ‘tribute’ edition of the LC4 by Charlotte Perriand, Pierre Jeanneret and Le Corbusier (see p56); Vitra (which has always traded on names such as George Nelson and Jean Prouvé) has relaunched pieces by Charles and Ray Eames and Alexander Girard; and, four years after his death, Robin Day appears to be popping up everywhere. The reasons for this obsession with the past aren’t hard to discern. The economic recession of 2008 sucked the wind out of the furniture industry’s sails just as it

was booming (or becoming ever more self-indulgent, depending on your point of view).

Personally the moment that summed up the sector’s decadence better than any other was the Established & Sons installation at the London Design Festival in 2007 where the company’s production pieces were reproduced in Carrara marble and hoisted on to 6m-high plinths. Towards the end of a cocktail-fuelled private view, a young woman staggered towards one of the exhibits and, leaning forward, threw her guts up over its base. Signs that the industry needed to recalibrate weren’t hard to see – or indeed smell – that evening.

Surrounded by the subsequent economic debris, it’s little wonder that manufacturers elected to revert to the tried and tested. It meant that any R&D and retooling would be spent on products with which consumers were already familiar, and that often tapped into a sense of nostalgia for an era that seemed more simple and optimistic. Arguably the most direct exponent of this has been the ever-canny Wayne Hemingway, who has not only launched a vintage-themed festival but produced a line of furniture for that most evocative of postwar brands, G Plan.

Is this something about which the design industry should be concerned? Well, yes and no is the honest response. For years, critics like me have been complaining that the furniture industry had become locked in an annual cycle that mimicked, if not exactly replicated, the fashion world. There can be little doubt that we’re becoming overrun with more and more stuff that often serves little purpose other than to provide the media with its craving for the new. If that is receding, we can hardly complain.

And there seems to me absolutely no reason why old designs shouldn’t be rereleased if they are genuinely worthwhile. If they can also be refined and improved with new materials and production techniques, like some of Dieter Rams’ pieces have been by Vitsœ for instance, then so much the better. A new generation of consumers should be introduced to great work. By the same token, there is a balance to be struck; if a manufacturer becomes overly reliant on the past, there’s a danger it falls into pastiche, which could make

it become a victim of the fleeting fashion the designers of its original pieces were attempting to avoid. Makers of mid-century modern furniture, you have been warned.