As any perfume lover knows, fragrance can influence our emotions, memories and even behaviour. Meet the designers for whom scent is an integral part of the creative process

There has been a marked shift in the design industry’s attitude towards multisensory experiences, and a growing understanding of the immense power they wield in shaping how we perceive an interior environment. Though thoughtful scenting is not new, it has been evolving towards a more integrated and functional story-telling role. This is no post-completion add-on of scented candles designed to simply smother the smell of office hardware and human toil. This is scent as an integral, functioning part of spatial design, teased and tailored for a scheme just as light or colour might be.

Image Courtesy of Jolie

“Neuroscience and behavioural psychology now allow us to measure the impact of olfactory qualities on people and the activities they perform,” says Anna Barbara, architect and director of an olfactive design course at Milan’s Politecnico postgraduate design arm, POLI. The course is newly conceived to equip architects, interior designers and planners with expertise in shaping air quality in its entirety, from the scientific mechanics to the science of perfumery. “Museums, retail, hospitality and company HR departments, as well as schools, universities and hospitals, are all increasingly interested in scent and its potential applications.”

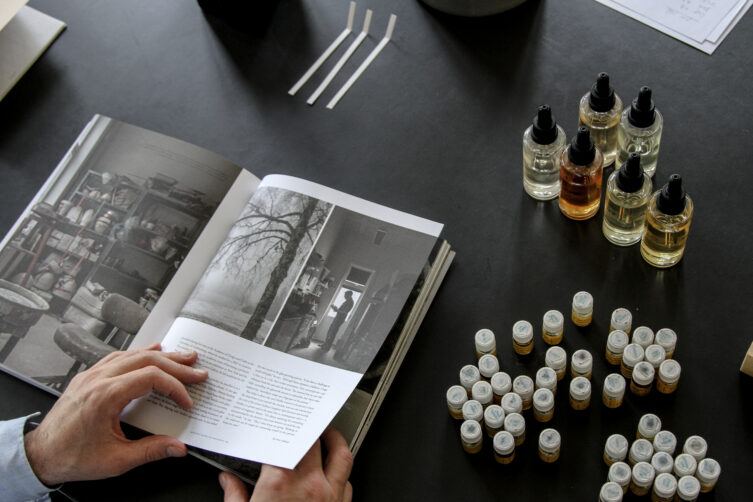

Photography by Manuel Kuschnig

Design studios around the world are responding to this burgeoning interest in spatial scenting. Based between Tokyo and an exquisitely designed studio in Berlin, Austrian-Japanese duo Shizuko Yoshikuni and Manuel Kuschnig of Studio Aoiro have been influencing our experience of spaces through olfaction for many years. They have moved away from Yoshikuni’s early naturopathic roots and traditional aromatherapeutic blending, with its sometimes earthy and over-punchy presence, towards subtler, less predictable compositions. “Creating identity through scent seemed to be one thing, and therapeutic functionality was another, so we thought, why not make a sandwich?” explains Yoshikuni. Their many projects include scenting opera houses and cars, museums and hotels. For VitraHaus in Germany, they worked closely with the designers on a scent for the lobby, which introduces a soothing sense of home with hints of the outside vegetation wafting into the transitional space. For the Reethaus immersive performance space in Berlin last year, they expanded on Austrian architect Monika Gogl’s raw, monastic design to create an aesthetically cohesive, deeply calming scent.

Photography by Sarah Bates

The co-founders of lifestyle store Earl of East, Paul Firmin and Niko Dafkos, meanwhile, have evolved into London’s go-to olfactory storytellers for creative brands and musicians. They also took a creative approach to scenting the co-living/working space The Collective [now closed] a few years ago. A signature smell to welcome you at reception was tweaked to prioritise the invigorating top notes in the gym area, dialled down to its comforting base notes for the social zone and, for the library, focus-inducing rosemary and sage were allowed to lead. But at no point was the scent symphony designed to take over. “For working or creating, when you need to focus, you don’t want anything overpowering,” says Dafkos. “You want a background hum – a constant that shuts down other smells and allows you to dive into a task without distraction.”

Image Courtesy of PineSkins

Also influencing the field are the designers developing new natural materials with minimal processing, which allows the smell of nature to come directly into spatial design. Latvian designer Sarmīte Poļakova, for instance, created PineSkins on the back of her Design Academy Eindhoven graduate project. The malleable, leather-like substance, made from the inner bark of pine trees, now clads a wall in Fora’s Jellicoe, the co-working space in London’s King’s Cross designed by Universal Design Studios. It combines texture, colour and scent to prompt a grounding sense of forest immersion. “People connect it with a feeling of being in a forest,” says Poļakova. “It doesn’t smell like wood in a wood store; it has this liveliness from the tannins. When you realise people respond well to it, you can start to work with that and explore how this could be part of the design of the project itself.”

Image Courtesy of Jolie

There is much to be gained by applying this holistic thinking to the design of office spaces. For Franky Rousell, interior designer and founder of Jolie Studio, olfactory considerations have become entirely integral to her design process. When she presents her initial ideas to a client, she arrives armed with vials of scent – aromas that she has carefully curated to underpin the story of her design concept. And it matters little that the client is a suited and booted developer with scant room in their life for fragrant fripperies – by the time Rousell leaves, they are usually talking more about the olfactive specifications of the design than the seating selection or interior colour palette. Rousell has honed her distinct design approach principally in office developments and hospitality venues; starting in Manchester, her studio now has a London outpost and a foot in New York. After studying architectural technology, she dug deep into the science of sensorial design, connecting with neuroscientists in Oxford and Cambridge to grow her understanding of the area. Now integration of sensorial design starts on day one at Jolie, when the team lays out a floor plan and zones it with a marker pen, recording where an environmental shift is needed. Three key emotions are assigned to each zone, allowing for crossover. They then submit to thousands of years of research around aromatherapy and fragrancing to evoke those feelings in scent (the emotional charting goes on to inform the wall colours, the texture underfoot and bespoke soundtracks).

Image Courtesy of Jolie

This was the method they used in Clarence House in Manchester, an office building that Jolie designed for the financial and legal sectors and their high-performing, high-pressured personnel. “There’s a power mentality among them,” explains Rousell. “The entrance lobby has a moody, dark-green interior, so we added a black tea blend, which is great for communicating aspiration, prestige and a sense of mystery, but also for reducing stress.” For recently completed offices at 2300 Market Street in Philadelphia, Jolie established a mood base-note – sandalwood – for its reassuring and grounding qualities, then built on it in different areas, adding uplifting bergamot, a natural antidepressant, for one area and jasmine, which stirs an excited emotion, in another.

Photography by Manuel Kuschnig

“Olfactory qualities have tone, volume, intensity, saturation and are as dynamic as any musical composition,” adds Anna Barbara, who is proudly training the next generation of space designers to build this additional aesthetic dimension into their projects. “They shape and give coherence to all our other sensory qualities.” This is no passing fad – it’s just the beginning of us opening our noses to olfactive design.

This story was originally featured in OnOffice 172, Autumn 2025. Discover similar stories by subscribing to our weekly newsletter here