Drake’s HQ combines showroom, stock room and offices in one|New Crittal windows restore a period look to the 1930s building|The traditional display cabinets were salvaged from the British Museum|Colour stands out against the monolithic, monochrome interiors|Glazed partitions allow the building’s various functions to better connect||

Drake’s HQ combines showroom, stock room and offices in one|New Crittal windows restore a period look to the 1930s building|The traditional display cabinets were salvaged from the British Museum|Colour stands out against the monolithic, monochrome interiors|Glazed partitions allow the building’s various functions to better connect||

Hawkins\Brown has re-imagined traditional working spaces for Drake’s Old Street HQ by removing partitions and connecting the floors.

The area around Old Street roundabout in east London has become synonymous with the tech industries. Christened the Silicon Roundabout in wry homage to California’s Silicon Valley, the distinction is an important one: whereas San Francisco’s technology and software companies inhabit large purpose-built business parks south of the city, London’s tech boom occupies disused office blocks and light industrial buildings in the city centre. All this makes the decision of a decidedly old-school company, tie-maker Drake’s, to move here from Clerkenwell, slightly incongruous.

Drake’s sought to unite its various business arms – a tailors, warehouse depot, back office and shop front – into a curving 1930s light industrial block and adjoining rectangular 1950s extension on the corner of Haberdasher Street and East Way. Drake’s director Michael Hill struck up a professional relationship with architects Hawkins\Brown through a mutual friend in the art world and commissioned the practice to transform the six-storey office into a mixed-use building, including a floor of speculative offices and penthouse apartments. Reminiscent of an era when shopkeepers lived above their premises, Hill and two fellow directors have taken three of the nine flats.

“We felt that the colour should come from the fabrics that make the products”

The building had suffered a similar fate to many of its ilk in post-industrial Britain. Clumsy uPVC windows combined with layers of grime to disfigure an otherwise handsome brick exterior. Formerly home to courier firm Lewis Day, the building’s originally generous proportions were adapted to suit its inhabitants’ working practices, in this case by the inclusion of suspended ceilings and an army of partition walls. Hawkins\Brown got rid of the plastic frames and replaced them with Crittall windows, a move prompted by a visit to Crittall’s factory in Essex. “They were fascinated with their manufacturing process,” says practice partner Nicola Rutt. The elegant profiling of the new frames reclaimed some of the building’s lost dignity along with a general cleaning up of the masonry. The architects also salvaged a vintage clock attached to East Way elevation, restoring it and placing it above the new showroom entrance on Haberdasher Street.

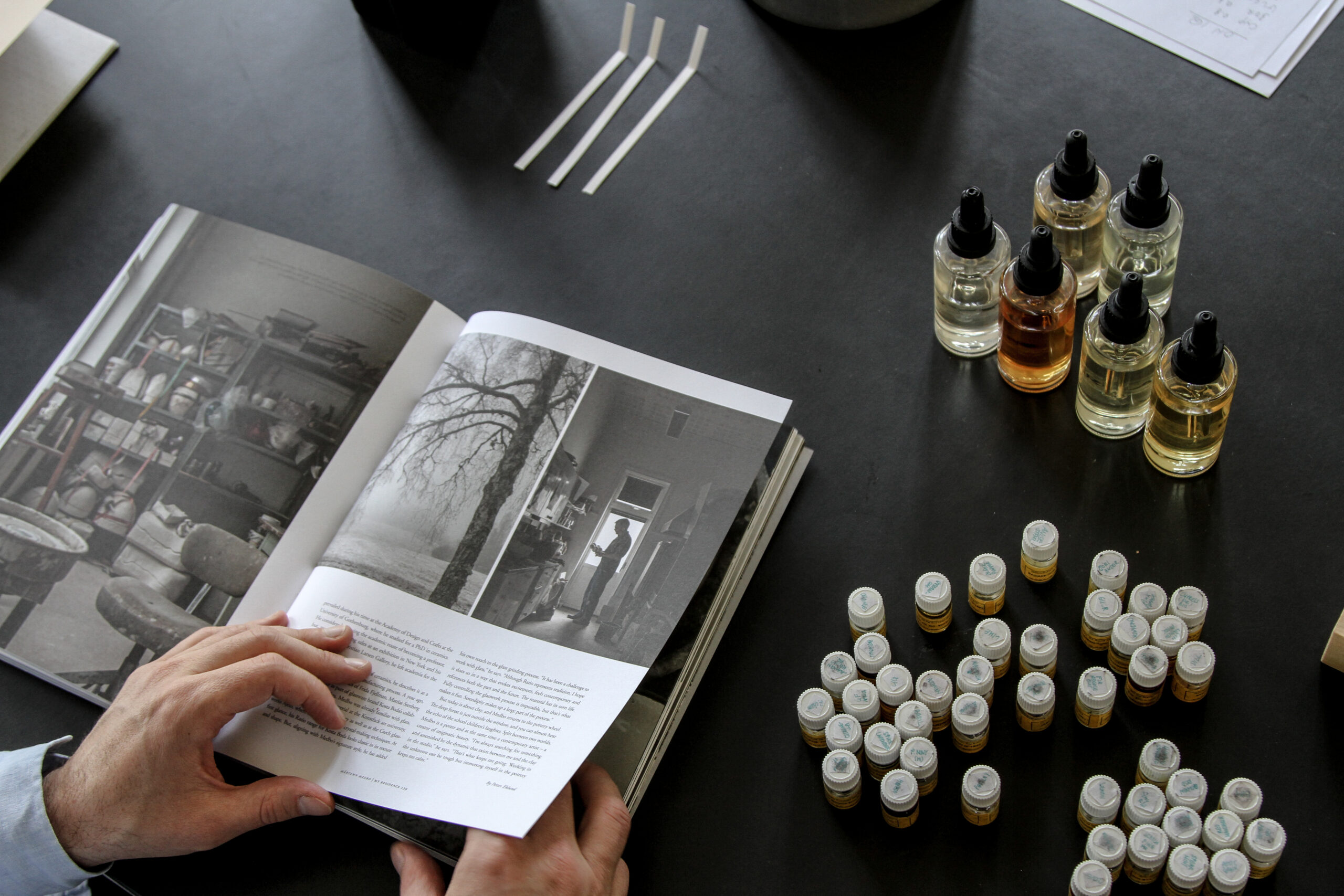

Having three separate entrances solved the challenge of navigation, with the apartments accessed from the East Way, and the spec office on the second floor serviced by an entrance on Bevenden Street. The Haberdasher Street entrance leads directly into Drake’s factory shop, where various ties and men’s accessories are housed in display cabinets sourced from the British Museum by way of salvage specialists Retrouvius.

Established in 1977, Drake’s is of pensionable age compared to the internet babies surrounding it, but nevertheless, the firm was keen to avoid traditional working practices. The onus was on transparency and flattening out the hierarchies, which saw Hawkins\Brown remove the partitions and install large windows (again Crittall) to connect the ground floor administration office with the distribution warehouse and factory shop. The suspended ceiling also faced the executioner’s axe, with the previously recessed lighting replaced by white pendant lights reminiscent of oversized ice-hockey pucks, intended to distract from the servicing. In order to increase the sense of space, the exposed ductwork bores through the concrete beams rather than moulding around them.

Elsewhere, the architects collaborated with Chris Tanner, operational director of Drake’s, on some monolithic black storage modules that, when coupled with the whitewashed concrete walls, create a monochrome aesthetic. “We felt that the colour should come from the fabrics that make the products,” says Rutt. A collection of Jean Prouvé tables and chairs populating the main meeting room continues the theme.

Architecturally, the most substantial intervention was the addition of a stair joining the ground and first floors. On the first floor, the architects have united the design and workroom facets of the business. Capitalising on the high levels of natural light, quality control is located at the far end of the office next to the windows, providing Hawkins\Brown with a natural starting point to arrange the rest of the floor. The production line begins by checking for imperfections in the material and continues in a linear fashion through trimming and sewing areas towards the design studio at the shop floor’s opposing end. A client meeting room for seducing potential buyers is nestled in the bullnose of the building.

Lining the Bevenden Street side of the office is a bright canteen kitted out with banquet-style tables to encourage staff to eat lunch together. Originally filled with random junk (mannequins and other oddities) the basement now serves as an extensive stock room.

With a tight budget, Hawkins\Brown has made a decent job of recapturing the building’s original spirit. These kind of refurbishments often necessitate a kind of architectural archaeology with the careful removal of layers of detritus to reveal the hidden gems. An excellent example is the original lift, which the architects managed to save from demolition. Most gratifying is that for once it is not a tech company occupying an old East End industrial building, but a manufacturer, joining the circle where it originally began.