Illustration by Sebastian Braun|||

Illustration by Sebastian Braun|||

Stuff is overrated. It piles up, it clutters, it often costs an arm and a leg, and with the baffling throwaway economy, it isn’t everlasting either. Over the past few years then, the modern consumer has been favouring experiences over possessions, those sweet intangible moments that leave us enriched and filled with memories. An out-of-the-ordinary dining experience, an interactive notebook-making class, a memorable concert at an unusual venue, when you distil the essence of it right down to its most fundamental purpose: an experience is measured by a reaction – good or bad – and the emotion it conjures up.

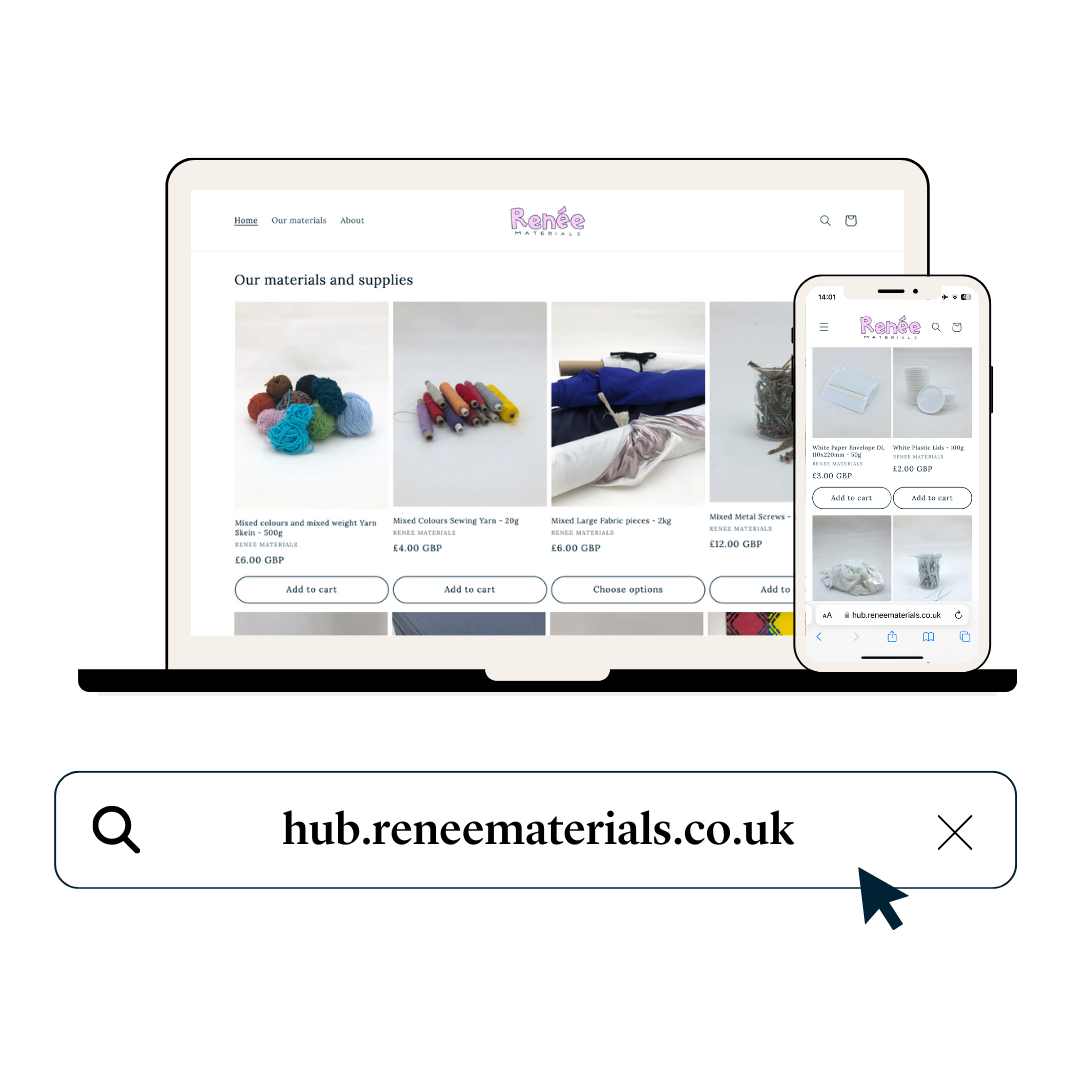

Unsurprisingly, the hospitality industry has been a direct beneficiary of the experience economy. In November 2017, global travel powerhouse Airbnb launched Trips, a platform for travel services that extended the company’s remit from accommodation to one of its new hallmarks – Experiences. Since then, Airbnb has accumulated 15,000 Experiences in over 1,000 markets, 800 of which are in the UK.

“Just as there is junk food and healthy food, there is mass travel and healthy travel,” an Airbnb spokesperson tells me. “Airbnb Experiences is an antidote to mass-produced tourism, enabling travellers to experience a different and authentic side of a city through the local people, giving unprecedented access to communities, places and things to do that you’d never know through traditional tourist travel.”

Hotel 50 Bowery with artwork by China-based Dake Wong

Hotel 50 Bowery with artwork by China-based Dake Wong

The stats are telling, too. At an equivalent stage in the life of the business, Airbnb has seen 21x the number of guests on Experiences compared to guests in Homes, and the number of active experiences on the platform has grown year on year by nearly 500%. In 2018, the most booked Experience categories have been food, nature and art, with London offerings counting a secret show at The Old Operating Theatre Museum & Herb Garret, urban trail running in Highgate, a bookbinding workshop and a myriad more.

A compelling expansion has also seen the company start Airbnb for Work, which now features experiences for professionals such as wellness, team-building and social impact. Since its 2014 launch as Airbnb for Business, it has seen 700,000 companies sign up their employees, with bookings tripling year on year. The Airbnb spokesperson explains that these perks are “an essential way to attract, retain and motivate top talent in today’s hyper-competitive talent environment”.

Airbnb saw the potential of experiences back in 2014, but when did the shift begin and why? Muriel Muirden, executive vice president and managing director of strategy at architecture firm WATG London, attributes it to equal parts millennials and baby boomers. “It started happening between five to eight years ago. The millennials started to come of age and be active travellers and constantly seeking out their Instagram moments in every aspect in their life. At the same time, the baby boomers stopped saving for a rainy day. They started demanding more of their vacations.”

According to Muirden, this “lust for experiences” is very much a global phenomenon among millennials. With boomers, she remarks, the focus is on the more “mature markets” versus some of the emerging economies that don’t have the disposable income. “It’s the more Western syndrome,” she says.

The art at Hotel 50 Bowery is deeply rooted in Asian culture

The art at Hotel 50 Bowery is deeply rooted in Asian culture

Interestingly however, Muirden points out that when you think experience, “you immediately think of an outdoor activity, but in fact experiences can be extremely close to home”. She lists eclectic artwork, soft furnishings, lighting and even scent – a multi-sensory approach to design that contributes to that intangible moment where architecture becomes atmosphere.

In March this year, the WATG-designed Lido House opened in the coastal city of Newport Beach, California. Its decidedly beach-house style and hyper-localised design involved preserving heritage trees and using a local landscape palette with tactile materials such as used brick, wood siding, trim work and ironwork.

On Newport Beach’s only rooftop terrace, WATG designed what it calls “the Ultimate Cabana” in a circular tower at the corner of the building and overlooking the city. In an architect’s book, this cabana is the wow factor; the Instagram moment that makes you want to dive in your pocket and share it with the world – the moment where tangible becomes intangible.

As Muirden highlights, a “wow factor” can span all five senses, but the type and scope of it hinge on target demographic and location. “We’re a curious beast, we crave the experiential but in different ways from work to play. Whereas we want the slimline and the no-fuss from our urban hotels, on our vacation experiences we want something that’s immersive, that connects us to the community.”

The Hyatt HQ’s “arrival area” is just like a luxury hotel lobby

The Hyatt HQ’s “arrival area” is just like a luxury hotel lobby

The element of connection is no stranger to urban hotels though. The new CitizenM hotel in New York (see p70) banks on connectivity through its open piazza and collaboration with a local street-art collective, while on that same street and further into Chinatown, Wimberly Interiors’ Hotel 50 Bowery, which opened last year, chose subway tiles in its rooms and showed its deeply rooted Asian culture by teaming up with Beijing-based street artist, Dake Wong.

Published in August 2018, WATG’s report, “New Luxury” Hotels: A new set of priorities, portrays this “shift in luxury spending away from the acquisition of ‘things’ towards the collection of experiences” as a clear win for the hospitality industry, but is this evolution notable in the workplace, too? Another report by the same firm suggests the parallels are striking.

“There are a lot of obvious linkages between hospitality and office environment,” says Muirden, who believes the “sense of arrival” in both sectors is a strong common denominator. “Making sure design works for comfort and wellness” is another one.

This time last year, London gained a hybrid space dubbed as a work and wellbeing destination. Mortimer House was inspired by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs theory, which New-York based AvroKO translated into design across the Fitzrovia co-working space’s eight floors, with a gym, yoga studio and ground floor restaurant at the foundation of the pyramid (the physiological needs of the individual). More a hospitality platform than a traditional co-working space, Mortimer House celebrates its one-year anniversary this month, and the merging of sectors is still spreading like wildfire.

Flexible working at the Hyatt HQ

Flexible working at the Hyatt HQ

Building on its research-led design approach, architecture and design firm Gensler recently released the so-called Gensler Experience Index, which quantifies the direct impact of design on great experience across retail, public spaces, workplaces and hospitality. Filipa de Albuquerque, workplace consultant at Gensler, explains what prompted the company to undertake a multi-year survey of 4,000+ that culminated in the publication of two reports in 2017 and 2018.

“The connection between business performance and great experience is well documented; we already know the importance of product, brand and service quality in creating a great experience,” she says. “However, no single piece of research to date has combined the known drivers of creating a human experience with design factors.”

To help us better understand the nature of human experience, the Experience Index suggests that understanding a client’s intention and how it frames their experiences is a key driver of the final design. The Index thus identifies five distinct categories, or “modes” of experience including Task, Social, Entertainment, Discovery and Aspiration. And while the first three are self-explanatory, the latter two are worth exploring, for they are perfect examples of intangible with a heavy dose of subjectivity sprinkled in the mix.

“Discovery mode is often killing time or space between other activities, and you’re looking to help someone have an engaging unstructured experience,” explains de Albuquerque. “Aspiration mode is about personal growth and connection to a larger purpose – joining a gym, getting inspired etc. Yes, there is certainly an unavoidable level of subjectivity to these discussions, but our research and data are showing us that ‘discovery’ and ‘aspiration’ modes exist, even if they’re more nebulous, and that solving them is a crucial piece of creating a great experience.”

A ground-floor eatery at Mortimer House

A ground-floor eatery at Mortimer House

Worth noting that while the five “modes” exist as separate entities, reality calls for multiple modes at once. And as the report states: “Supporting easy mode-switching is a key aspect of creating a great experience”. Gensler’s proposal for Hyatt’s Chicago headquarters portrays this plurality of modes rather perfectly.

Bringing all corporate employees under one roof and designed in collaboration with Hyatt, the so-called Hyatt Hub builds on the company’s culture of care by combining the best attributes of private offices with those of open-plan environments, with a striking arrival area, social spaces aplenty, dual-purpose coffee and bar areas, private work suites and more.

That a holistic approach like that of the Hyatt Hub is the way forward is a no-brainer, but also an irony of sorts when seen through the lens of the “Insta-culture”. How many hotels cater for the design of the back-of-house as much as the front-of-house? If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?

WATG’s Muirden is adamant: “To make this machine work efficiently, we need to look behind the closed doors.” Perhaps hotels, stores and workplaces alike should let the public in beyond the facade then, and show us what they’re truly made of. Any takers?

As AirBnB’s Experiences grows and grows, is it part of a wider shift towards design focused around users’ emotional responses?