||

||

Developer Jonathan Carr’s Bedford Park, London’s first garden suburb, was ahead of its time in creating community-focused new housing. On the centenary of his death, his legacy should be remembered

This year is the centenary of the death of the developer Jonathan Carr. Not many people may know that, but they should: the legacy of this brilliant but financially dodgy Victorian is hugely relevant to housing and planning in London today.

Carr was the developer of Bedford Park in Chiswick, dubbed “the first garden suburb”. Sir John Betjeman described its red-brick houses and leafy streets as “the most significant suburb built in the last century, probably the most significant in the Western world.”

In Hermann Muthesius’ 1904 Das Englische Haus, the author wrote: “There was at the time virtually no development that could compare in artistic charm with Bedford Park, least of all had the small house found anything like so satisfactory an artistic and economic solution as here.”

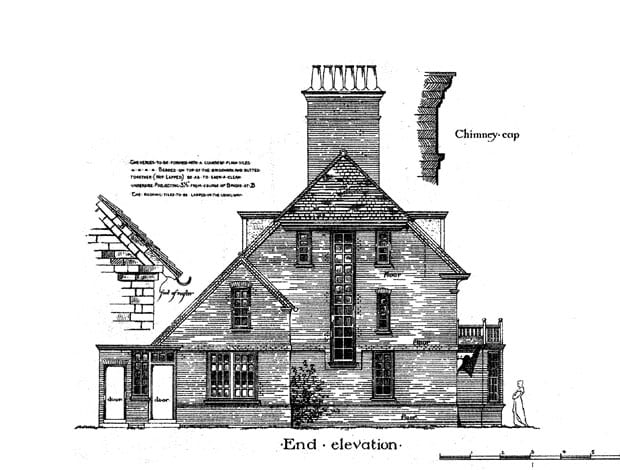

Built between 1875 and 1886, Bedford Park is built in the Queen Anne Revival style, much of it by Norman Shaw using a handful of designs that were repeated across the estate. This gave variety and interest to the streets, allowed customisation for occupiers who leased off-plan and introduced a level of efficiency into construction and planning.

Bedford Park was an inspiration for the creators of later garden suburbs and cities. Although it was a commercial development and lacked the planned social structure of Hampstead and Welwyn, Carr provided a church, stores, a pub (in contrast, Hampstead was teetotal and had tea rooms) and a club that became the core of the new community. Sir Peter Hall praised the suburb’s “dendritic” layout, focused on the Underground station at Turnham Green, creating an ideal walking and cycling community.

After a decade of developing in Chiswick, Carr moved closer into town to build a series of houses in Kensington Court. These were innovative in that they included an accessible conduit that carried all the services in the street and were served by their own local electricity generators and hydraulic pumping stations. If only this had caught on – we wouldn’t have to keep on digging up streets, and localised energy delivery would be so much more sustainable than the current grid system.

We wouldn’t have to keep on digging up streets & localised energy delivery would be much more sustainable

Sadly, Carr got into financial trouble in Kensington; the development ground to a halt and he had to sell his interests in Bedford Park. Undaunted, he built Whitehall Mansions, a huge block in the French Renaissance style overlooking the Thames.

Its homes were a model for inner-city living, operating more like serviced apartments – none of which had kitchens – with communal dining facilities (now the premises of the Farmers Club). This, too, turned out to be a financial disaster and Carr retired hurt to a rather grand house he had built for himself at Bedford Park (now sadly demolished). But he hadn’t given up and tried to get an idea off the ground for a model community in Grove Park, part of the Duke of Devonshire’s estate. The square plan and gridded streets were in stark contrast to the villagey feel of Bedford Park; but it came to nought.

Carr’s fiscal issues did nothing to help his reputation. A recent book on him by D W Budworth is subtitled Only Begetter of Bedford Park and Subject of a Record 352 Bankruptcy Petitions. Yet Carr’s work has so many lessons for the delivery of housing and successful communities today, when new settlements, new garden cities and more housing are on the agenda, that we should take note of his work and remember his legacy.

More from Peter Murray

Peter Murray on tall builidings & greenery

Is London’s greenbelt overprotected?

Peter Murray on the current housing shortages and the modernist fundamentals of John Habraken