The reflective glazing of the new D9 building maintains R&D privacy|||

The reflective glazing of the new D9 building maintains R&D privacy|||

Is it a bird? No, it’s a plane – an English Electric Lightning jet to be precise – suspended in the air. We’re in the Lightning Cafe, part of Dyson’s new £250m technology campus in Malmesbury, along the M4 corridor in Wiltshire, with swish new research and development and sporting facilities. Such British irreverence is what has made the engineering brand a success. Describing this new chapter, founder James Dyson himself says: “Bolstering our in-house testing facilities, these new spaces allow engineers to continue to boldly develop new technology, learning through every failure.”

The architectural firm behind the scheme, WilkinsonEyre, has a longstanding relationship totalling some two decades with the company that gave us the Airblade hand dryer, the nifty new Supersonic hair dryer and of course that famous bagless vacuum cleaner. The Dyson factory and headquarters buildings were completed in 1999, and in 2012 the practice was asked to put forward a new masterplan that would spread the campus to the south and west of the existing site, providing 12,000sq m of new R&D facilities. This is, after all, a client that spends £5m on research and development. The site now extends to 23ha and more than 3,000 people call it their place of work.

The Hangar houses up-to-the-minute sports facilities

The Hangar houses up-to-the-minute sports facilities

So we donned our press armbands (a first in my journalistic career) and weaved our way through the surprisingly hipster-looking crowd in these new canteen facilities to the conference room on the first floor. No white coats to be found here, or if there are, they’ve left them in one of 129 advanced research laboratories in what they call the D9 research and development building, which totals 8,000sq m in area.

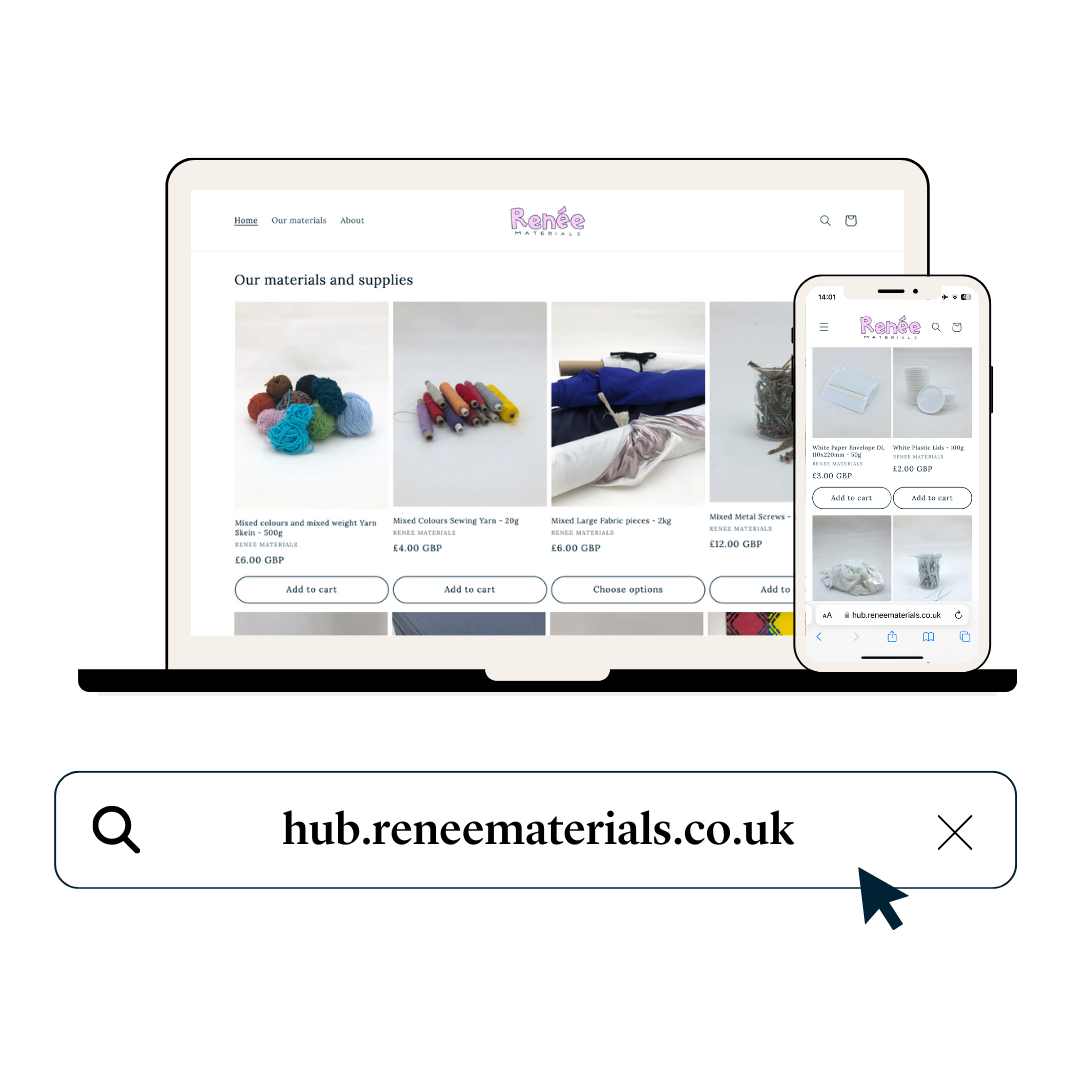

Dyson CEO Max Conze takes up the story, “Spaces are vessels,” he says. “For 20 years, a powerful coherence has been created: where we make technology is something quite magical.” As the non-disclosure agreements are signed, it’s clear security’s a pretty high priority for Dyson. The Lightning Cafe is intended for visitors to be brought to from reception, avoiding the chance of a peek into anywhere else. It has an easygoing airy and transparent feel, with its double-height space. Opposite the cafe, the D9 has reflective glass to keep prying eyes out, while still allowing outward views and natural light.

Landscaping leads out to the campus perimeter Nature Walk

Landscaping leads out to the campus perimeter Nature Walk

Light is a key theme throughout the scheme. Jake Dyson, James’s son, has established a reputation for innovative lighting. Last year his eponymous company became part of Dyson and the Dyson Lighting category was born. Jake’s designs can be found throughout this project. He explains: “We thought a lot about the quality of light and long-lasting performance lighting. We also put a lot of work into the glare and how to illuminate surfaces.”

The trick, Jake explains, was combining task lighting with indirect illumination. The drone-like Cu-Beam suspended lights cast a wide pool of light across the ceiling in their uplight version and focus on particular areas in the downlight version. In the D9 building, there is the Duo version, which provides both up and down light in one fixture – clever huh? To complement this, Dyson’s CSYS task lights give individuals greater control of how their space is lit.

Lighting and detailing within the D9 building give a calm neutral look

Lighting and detailing within the D9 building give a calm neutral look

And, as you’d expect from a firm that prides itself on original, quality designs, there’s no skimping on specification – I spy a bit of classic USM storage, some Vitra Alcoves in royal blue and Herman Miller Sayl chairs. The interiors facilitate flexible working, combining workstations with laboratory facilities to allow for discourse and brainstorming, while a central atrium brings daylight into both the desk space and breakout areas. “Dyson takes the approach to seeding ideas. It’s much more about experimenting,” Jake Dyson says.

The architects’ brief included enhancing the surrounding landscape to increase privacy and prevent direct views into the buildings. This intertwines with another objective: health and wellbeing. The greenery connects to the existing Nature Walk around the perimeter of the site so the boffins can get a bit of a breather. Also tapping into this need is the new Hangar building for sports and leisure, its floor – Olympic grade no less, we’re told – laid out in a baffling number of white lines for different sporting configurations including basketball, tennis and badminton: an enviable bit of fitness kit.

A jet is suspended above diners in Dyson’s airy Lightning Cafe

A jet is suspended above diners in Dyson’s airy Lightning Cafe

It’s a lifestyle more than just a building,” muses WilkinsonEyre founder Chris Wilkinson on the train home from our visit. The wavy roof of the original building was more than an architectural flourish, he adds: “It was a way of getting planning consent, as it floats.” The new additions have their own architectural charm too – Wilkinson talks of a “delicate filigree type of staircase” which can be found on one side of the D9.

Dyson very much remains a family business but now has facilities that rival a Californian campus. And it is clear that, as Wilkinson adds in summary, the project “serves the technical and social needs of their creative young workforce”.

WilkinsonEyre’s expansion of the Dyson campus mirrors its client’s precision approach