||

||

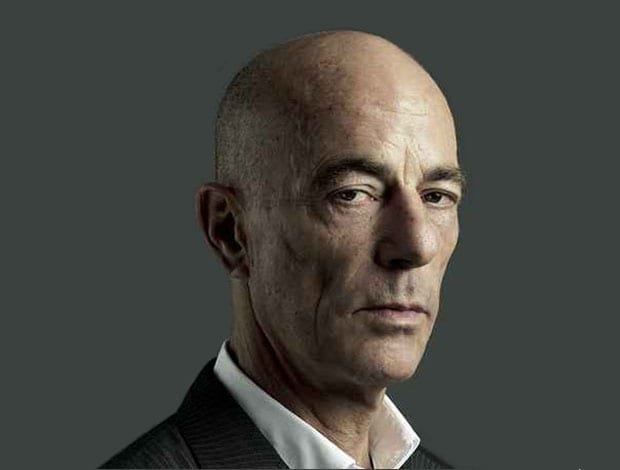

Jacques Herzog, co-founder of Swiss architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron, talked to Design Museum director Deyan Sudjic last night in the latest instalment in the museum’s What Next? series. They spoke about the practice’s soon-to-be-completed headquarters for BBVA in Madrid; his fascination with materials; the firm’s unique collaborations with artists; and its work on the Tate Modern and the Beijing Olympic Stadium

Deyan Sudjic: What is the world view from Basel?

Jacques Herzog: It’s a small city and country, but it has Art Basel and other shows like that, so it’s an important global destination. From very early on, we tried to think about what the city is becoming and its potential; to think about it in an urban context.

DS: It’s quite a matter-of-fact place, isn’t it? Cool, logical…

JH: I think that’s a good thing. It’s practical. A contract is a contract; craftsmanship is craftsmanship. I think that’s evident in our early buildings. We were concentrating on bringing back the core qualities of architecture; they are physical places built for people.

We’re working on a high-rise building in Basel at the moment (Roche Building 1 – pictured below) and it’s a big responsibility to densify a small city. In London this would not be such a phenomena because there are others like it, so it’s about how to do this in a way that people will like it. It is an urbanist and socialist challenge.

DS: Let’s talk about materials, because you are fascinated with materials aren’t you?

JH: Architecture is physical, so to not take the variety of materials as a serious thing would be a missed opportunity. The whole Ricola building (the recently completed herb processing plant, Herzog & de Meuron’s seventh building for the Swiss sweet maker – pictured below) is made from rammed earth. It’s a fantastic material, especially as it’s in Laufen, which has very good clay.

To work with this material is a wonderful experience – the smell, the touch, it’s impressive. When you stand in front of the building, it has a raw quality that is rare today. We have sometimes been accused of being decorative. If you look at the Ricola building it could look like a palazzo, but close up it is like a façade of shelves, it’s minimal.

DS: In a world obsessed with digital, this is so contrastingly natural…

JH: We have to accept the digital world, but [people] love materials. They bring us back to reality. Whenever you can use physicality as an architect, I believe you should. For example the De Young Museum [in San Francisco] is clad in copper. It has beauty when it ages so it changes over time, and you can give it texture.

DS: And what about the Dominus Winery [in Napa Valley, California]? Lots of people still talk about that.

JH: In that case the materials were there already, the volcanic stone. The gabions [wire containers filled with stones – pictured below] work well. It was a technology that existed, but we used it in a way that’s never been done before. It represents the contrast between something so heavy that’s also permeable.

DS: Your studio has grown somewhat since then, you’re at around 450 now.

JH: The truth is we could’ve been bigger if we took on every commission but we’ve ben very selective. It’s not just the amount of people but the amount of projects, and we need to oversee them all.

DS: What are you working on now?

JH: We’ve been working on the Helsinki Dreispitz in Basel for a few years, which includes a building for our own archive of models, drawings and materials (pictured above). This area is becoming a new neighbourhood, with an art school and some offices. This building is helping to get it started, to trigger something bigger than the project itself.

Also, the [Spanish bank] BBVA’s headquarters (below) in Madrid is almost finished. It’s near an airport, so we wanted the project to be built like a city. We cut into the existing building in a motion that is quite aggressive to integrate it with the wider site, then we surrounded it with a plaza. We like to do offices because it is usually a world that is so fixed.

DS: Tell us about your relationship with Joseph Beuys.

JH: He inspired me and Pierre (de Meuron) when we left architecture school. We had never met someone like that. Everything in his studio was super beautiful and well maintained, it smelled of grease and felt and copper.

I tried to be an artist, but I gave up because it wasn’t going to take me where I wanted to go. Architecture was opening more doors.

Architecture can be like art, but the role you have is very different. I think architecture that tries to be like art doesn’t work. But I think that’s why we can design a space for art, because we were so close to art and we knew artists, what they liked and what they hated. Everyone should stick to their fields.

DS: But you have worked with artists haven’t you?

JH: There are artists who have collaborated and the projects would not be the same without them. Ai Weiwei walked into our office in Basel and encouraged us to go to Beijing and go for the [Olympic] stadium project (above). He is so proud of that stadium.

Colour is difficult in architecture and often doesn’t work because it’s driven by aesthetic preferences. That’s why we work with artists because they understand colour.

DS: Now seems a good moment to talk about the Tate Modern…

JH: What is amazing is how [the client] saw what this could be. The Tate project was not so long ago, 20 years, and look at the dramatic change a city can take and the impact an art project can have. The Turbine Hall was meant to be this cathedral like space, it would be a shame to fill it. It’s a space no other museum will ever have, and a great place to show public scale artwork.

DS: Can you tell us why the new extension has changed from glass to brick?

JH: It was far too overwhelmingly different in glass. The client didn’t want it to seem like a different building. So we were happy to change it to brick. I think architecture is based on constraints, you can’t use it as an excuse for something not working, it’s a base condition. It has a client, it has money, it has a site. Stupid people think they need more freedom to create but constraints define us.

A good client represents the constraints in the best possible way. The Tate is perhaps not the best example, but Ricola and Prada have come back numerous times so it was obviously not such a bad experience (laughs).

DS: You have so many projects now, what makes you keep fighting for them?

JH: These projects are our view of how the world works. Each one is a learning curve. We get projects now that will significantly change the social environment, so we feel we can make a difference.

Audience question: Beijing has changed a lot over the past few decades and people say it is a playground for international architects – what do you think?

JH: The Chinese government has destroyed so many beautiful heritage buildings, and Beijing has changed so much, not because of international architects but because of the political mindset. Less attention is being paid to the history.

Actually an Olympic stadium is a stupid thing because it’s just for a few weeks, which is why the post Olympic programme is so important. We were commissioned to build a hotel and other things for the site, but that’s not happened because they make so much money from people visiting the park.

Audience question: What do you think about the relationship between architects and engineers? Is it important for architects to understand that side?

JH: As an architect you can only do more if you know more about the social issues and structural issues. If you know nothing about that, you’re just a decorator.