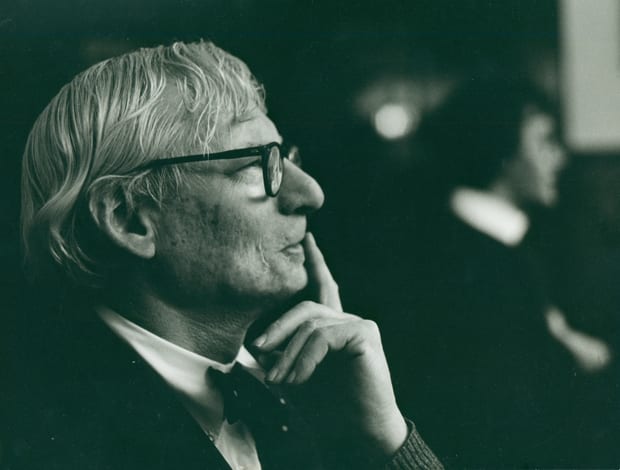

Louis Kahn, 1972 ©Robert C. Lautman Photography Collection, National Building Museum|The National Assembly Building in Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1962-83 ©Raymond Meier|Library of Phillips Exeter Academy, New Hampshire, 1965-72 ©Iwan Baan|Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, 1959–65 ©John Nicolais|Yale University Art Gallery, Connecticut 1951-53 ©Elizabeth Felicella|Franklin D Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, New York, 1973-2012 ©www.amiaga.com|Kahn’s former assistant Imtiaz Mia at the National Assembly building ©Robert Richman|Louis Kahn and employees model making, late 1960s ©George Alikakosdman||

Louis Kahn, 1972 ©Robert C. Lautman Photography Collection, National Building Museum|The National Assembly Building in Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1962-83 ©Raymond Meier|Library of Phillips Exeter Academy, New Hampshire, 1965-72 ©Iwan Baan|Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, 1959–65 ©John Nicolais|Yale University Art Gallery, Connecticut 1951-53 ©Elizabeth Felicella|Franklin D Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, New York, 1973-2012 ©www.amiaga.com|Kahn’s former assistant Imtiaz Mia at the National Assembly building ©Robert Richman|Louis Kahn and employees model making, late 1960s ©George Alikakosdman||

Architect, artist, inspiration, perfectionist and brick whisperer: the Design Museum’s new exhibition on Louis Kahn examines the enigmatic character’s life and work, and sheds light on his idiosyncrasies.

Architect Louis Kahn’s importance to modern architecture has been compared to Le Corbusier. His obituary in the New York Times described him as having been one of America’s foremost living architects. Yet he died of a heart attack, alone and bankrupt, in a toilet at Penn Station, New York, in 1976. His body remained in the morgue, unclaimed, for four days.

The Design Museum‘s retrospective Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture helps to piece together these disparate views of his life, and explores his legacy and influence on modern architecture.

Born in Estonia at the turn of 19th century, Kahn’s family emigrated to Philadelphia soon after. His early work largely consisted of modest local housing projects in his hometown and his first major building, the Yale Art Gallery, wasn’t completed until he was in his 50s. Other major projects include the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, designed to be a facility “worthy of a visit by Picasso”; the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, and the National Assembly Building in Dhaka, Bangladesh. His design for the Roosevelt Memorial was posthumously completed in October 2012.

Kahn used innovative construction techniques to design buildings that project an elemental, primitive power and believed in architects having a social responsibility. The exhibition reveals his huge influence on contemporary architecture in a series of interviews with three Pritzker-prize-winners Frank Gehry, Renzo Piano and Peter Zumthor, and Sou Fujimoto, whose design for last year’s Serpentine Gallery summer pavilion.

“Louis Kahn is unique, not just in going the opposite way to modernism, but in going much deeper to overcome modernism,” said Fujimoto. “So maybe our generation could be inspired by this kind of really fundamental, not primitive, viewpoint to rethink the whole history of architecture. Louis Kahn is still alive for us to create such inspiration.”

Numerous explanations have been mooted for his fall from grace. His work is hard to pigeonhole, being neither modernist nor a precursor to post modernism; he did little to ingratiate himself with clients; and was given to “strange quasi- religious utterances”.

As a teacher at Yale, he encouraged his students to seek inspiration by engaging their materials in conversation. In the 2003 documentary My Architect: A Son’s Journey by Nathaniel Kahn, he can be heard saying:

”If you think of Brick, you say to Brick, ‘What do you want, Brick?’ And Brick says to you, ‘I like an Arch.’ And if you say to Brick, ‘Look, arches are expensive, and I can use a concrete lintel over you. What do you think of that, Brick?’ Brick says, ‘I like an Arch.’ And it’s important, you see, that you honour the material that you use… You can only do it if you honour the brick and glorify the brick instead of shortchanging it.”

Kahn never carried out any building projects in Europe and, as a result, his name is even less well known in the UK. The Design Museum hopes this exhibition will change that.

Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture runs from 9 July – 12 October at the Design Museum, London.

My Architect – A son’s journey from S e n t i r A r k i t e c t u r on Vimeo.