Sculptural, geometric and expressively modern are not adjectives usually attached to town halls. But the town of Viborg, in Denmark’s Jutland, decided to discard any notion of archaic pomp when commissioning a building to house the 900 employees and public-facing services central to its administration.

The need for the new building, which was designed by Henning Larsen Architects, came from a reorganisation of boundaries within the country that brought about a fusion of five municipalities in Viborg. Henning Larsen Architects’ project manager Werner Frosch explains, “Viborg is the only town in Denmark that dared to commission a new building; the other municipalities just kept the old town halls and so decentralised their administration. Viborg took this brave step to make their administration more effective by concentrating it in one spot.”

The architectural competition brief for the project was similarly open-minded, and aside from the practical considerations of creating a 19,400sq m energy-efficient space, focused on the imagination of the municipality’s staff and creative freedom for the architects.

“The brief was a combination of a normal functional programme and some storytelling, where workshopped ideas from the employees shared how they could imagine their new town hall,” says Frosch. “These small stories were very good for us – it helped understand what their interests were.”

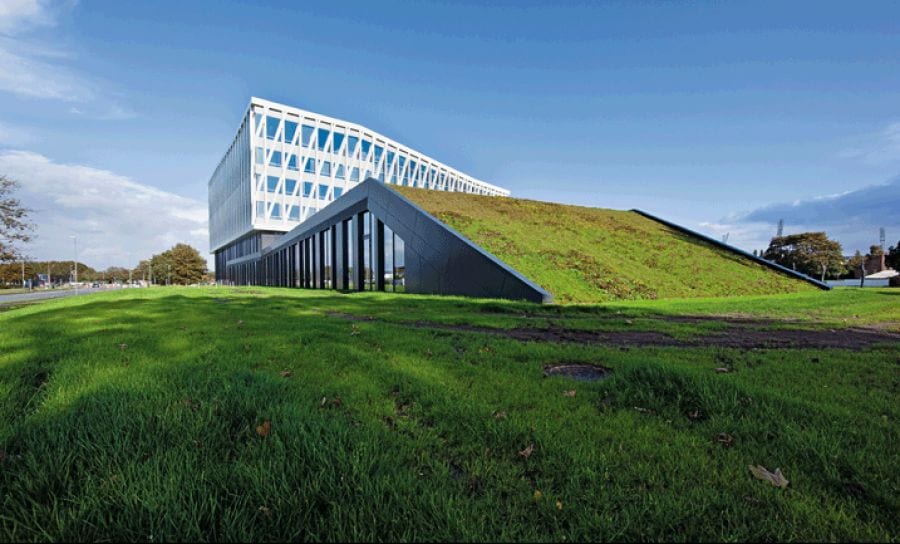

Based on a former military area on the outskirts of Viborg, the town hall sprawls beyond its cubic white centre, with three black fingers topped with turf, solar panels and thermoactive slabs. Frosch says: “The overall concept is that these landscape elements with their green roofs relate to the landscape to create a flow in to the central space. You come from the building and then flow out to the landscape.”

Based on a former military area on the outskirts of Viborg, the town hall sprawls beyond its cubic white centre, with three black fingers topped with turf, solar panels and thermoactive slabs. Frosch says: “The overall concept is that these landscape elements with their green roofs relate to the landscape to create a flow in to the central space. You come from the building and then flow out to the landscape.”

Rhombic paving forms lead visitors into the space, their geometric shapes reflecting the angles presented in the building’s facade. Keen to make the building the centre of the new municipality, Henning Larsen Architects created a path that leads from the centre of town all the way to the white cube’s door.

The “fingers” house the more public parts of the administration, as do the bottom two floors of the building, which include cafes, meeting rooms and a conference centre. Frosch explains: “On one hand you want to have the contact between the administration and the people of the city – to make this ‘the people’s house’ – but on the other hand you have to make sure the employees aren’t disturbed by the noise and the attendance from the guests. We made a kind of hierarchy, with areas that are very public, and areas that are semi-public and private, to ensure the security of the employees working here.”

Inspired by employees’ suggested descriptors of “flexibility, innovation, pluralism, coming together”, Henning Larsen created an impressive entrance to the building that felt like an “embracing figure”, says Frosch. The sculptural atrium features impressive views of the stairs that lead to each floor, the decks of which have been cantilevered differently so that no two views are the same. Frosch adds: “People say that when they come to the building they don’t expect this space, as you can’t see this embracing atrium from the cube outside.”

Modern-looking chrome and white plastic chairs complement the minimal grey, white and black surfaces and sans-serif typography of the reception. Leading up to the first floor from the grey stone of the ground floor is a statement staircase: Frosch likens it to a Greek Agora, a central meeting place for all. Presentations can be made from its summit, and visitors can rest on its central avenue of plush seats. “It’s a waterfall of wood coming towards the ground floor,” says Frosch. “The seating elements are soft cushions and we wanted to have bright colours to differentiate from the atrium’s white, and to bring a fun element.”

Modern-looking chrome and white plastic chairs complement the minimal grey, white and black surfaces and sans-serif typography of the reception. Leading up to the first floor from the grey stone of the ground floor is a statement staircase: Frosch likens it to a Greek Agora, a central meeting place for all. Presentations can be made from its summit, and visitors can rest on its central avenue of plush seats. “It’s a waterfall of wood coming towards the ground floor,” says Frosch. “The seating elements are soft cushions and we wanted to have bright colours to differentiate from the atrium’s white, and to bring a fun element.”

Frosch continues: “We aimed for precise direction of colour in the building; elsewhere we wanted it quite neutral. We preferred the colours to come from the quality of the materials – the wooden floors, the carpets, the stone floor on the ground – rather than from paint.”

The vast six-storey space is lit with a “star heaven” of cosmos-conjuring spot lights, and hidden strip lighting along the stairways to accentuate the edges of the floors and underpin the building’s sculptural form. The plaster walls have been optimised to absorb the acoustics of the public spaces, and the aluminium laminate ceilings included integrated light apertures, which can be opened to naturally ventilate the entire building.

The open-plan office spaces have been carefully positioned as close to the facade – and as far from the atrium – as possible, to harness natural light and minimise noise. Glass panelling separates staff from the central atrium to prevent the sound of public events seeping in, but it also gives employees an awe-inspiring internal view. Working with design consultancy Signal Arkitekter, Henning Larsen Architects created a number of flexible workspaces, including conference rooms, public meeting rooms, social consulting areas and, on the top floor, a large staff cantina and open roof terrace.

Monochrome desk furniture, in groups of six to eight workstations, has been supplemented with white laminate bar tables and bar stools, and ivy-green and scarlet upholstered egg chairs for informal meetings. There is only one closed office, which naturally belongs to the mayor, and it has been designed in a similar minimalist and monochrome format.

Frosch sums up his ambitions for this antidote to the traditional town hall: “From the six storey-high atrium, to the views from individual desks, we wanted to make something incredibly special – to give the experience of a new kind of administration for Viborg.”